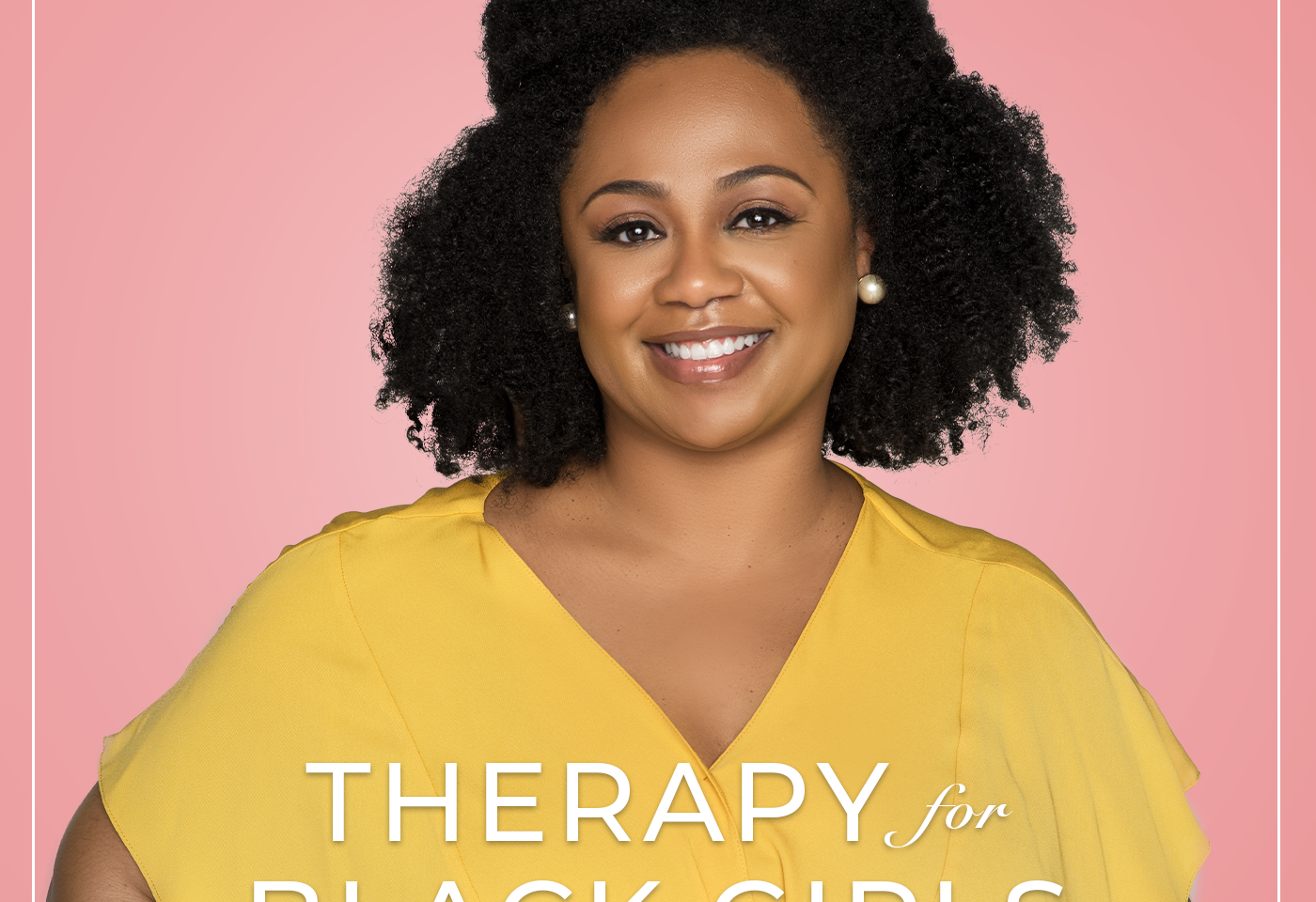

The Therapy for Black Girls Podcast is a weekly conversation with Dr. Joy Harden Bradford, a licensed Psychologist in Atlanta, Georgia, about all things mental health, personal development, and all the small decisions we can make to become the best possible versions of ourselves.

As therapists, much of how we work with clients is informed by our own interests and the things that help us make sense of the world. Today Dr. Lana Holmes joins us to talk about how her interest in horror movies informs her work and what the horror genre can teach us about trauma and survival. Dr. Holmes and I chatted about how she uses themes from horror films in therapy with some of her clients, how horror films might help us process issues like trauma and racism, and how to process triggering images you might see in a film.

Resources

Visit our Amazon Store for all the books mentioned on the podcast!

Join us for the Last Days of Summer Book Club chat on Aug. 26 @ 7pm EST. therapyforblackgirls.com/bookclub.

Where to Find Dr. Holmes

https://www.inclusivetherapywellness.com/lana

Facebook: @onwardtherapy

Stay Connected

Is there a topic you’d like covered on the podcast? Submit it at therapyforblackgirls.com/mailbox.

If you’re looking for a therapist in your area, check out the directory at https://www.therapyforblackgirls.com/directory.

Take the info from the podcast to the next level by joining us in the Therapy for Black Girls Sister Circle community.therapyforblackgirls.com

Grab your copy of our guided affirmation and other TBG Merch at therapyforblackgirls.com/shop.

The hashtag for the podcast is #TBGinSession.

Make sure to follow us on social media:

Twitter: @therapy4bgirls

Instagram: @therapyforblackgirls

Facebook: @therapyforblackgirls

Our Production Team

Executive Producers: Dennison Bradford & Maya Cole

Producer: Cindy Okereke

Assistant Producer: Ellice Ellis

Session 222: How Horror Films Help Us Process Life

Dr. Joy: Hey, y'all! Thanks so much for joining me for Session 222 of the Therapy for Black Girls podcast. We'll get right into the episode after a word from our sponsors.

[SPONSORS’ MESSAGES]

Dr. Joy: As therapists, much of how we work with clients is informed by our own interests and the things that help us make sense of the world. Today, Dr. Lana Holmes joins us to talk about how her interest in horror movies informs her work and what the horror genre can teach us about trauma and survival.

Dr. Holmes is a licensed clinical psychologist based in the Metro-Atlanta area. She's passionate about providing therapy that welcomes and celebrates marginalized, oppressed and stigmatized communities. Her collaborative approach to treatment tailors evidence-based interventions to the needs of people engaged in clinical work. Plus, as a big nerd, she's not above dropping a pop culture reference to illustrate a clinical point. Dr. Holmes offers teletherapy to individuals in Georgia as well as 22 other states.

Dr. Holmes and I chatted about how she uses themes from horror films in therapy with some of her clients, how horror films help us process issues like trauma and racism, and how to process triggering images you might see in a film. If there's something that resonates with you while enjoying our conversation, please be sure to share it with us on social media using the hashtag #TBGinSession. Here's our conversation.

Dr. Joy: Dr. Holmes, thank you so much for joining us today.

Dr. Holmes: You're welcome. Thank you. You are doing the Lord's work, Dr. Joy, I'm just happy to be a part of it.

Dr. Joy: Thank you. I appreciate you spending some time with us today. You study a lot about like trauma through the lifespan and what that looks like throughout our lives and you also are doing this really cool work, I think, around horror movies and how they are supportive in your work of trauma. Can you tell us a little bit about how you got into that and what that looks like?

Dr. Holmes: Yeah. For me, I grew up with horror movies, my mom was a big horror movie fan so I watched classics from like Halloween, Nightmare on Elm Street, but also Lost Boys was my personal favorite and The Shining, etc. I used to be terrified of it when I was a kid but it was around my teens I actually was able to get like deeper into it. And one of the things is that within the horror genre, and within a lot of fans before, we always talk about how horror essentially is an allegory for the things that terrify us as human beings. And that monsters and characters in horror media often are symbols for the things that horrify us in our lives. Like what could be more horrifying in real life than trauma?

And so for me, pretty much I've used horror as well as pop culture in general as a way of kind of illustrating certain concepts in trauma. Kind of like what you are doing because I think sometimes when you talk about these topics when it's related to mental health, it can seem really heavy and people are like, I don't really know how that really applies to me or how to translate that into my lived experience. But if you're able to use examples in the arts or in media, it's something that people can picture a bit more and it's a bit more illustrative in terms of being able to make those points.

Dr. Joy: Hmm. This may be a complicated answer or there may not be an answer at all, but when you think about like going towards the thing that you're afraid of (in terms of entertainment) that does not seem like a logical step to me, right? Like that I'm horribly afraid of this thing but now I want to spend two hours engrossed in this thing and I find that entertaining. Can you explain just a little bit about the psychology of horror and like why some of us, at least, find that entertaining?

Dr. Holmes: I think on a basic level it provides like the safe environment to confront your fears. Because I think most people, even if they're petrified of horror films, they can go in and they know like this isn't real, this is not going to happen to me, this isn't happening to me in real time. But I can be able to withstand an hour and a half to two hours of watching these things that are really frightening, and be able to confront my fears. And essentially, it's a great exposure or gradual desensitization, or even flooding in certain cases, of just being able to approach as opposed to avoid the things that you're afraid of.

And I mean, even though I'm sure people don't break it down this way, when you expose yourself to something you're afraid of, even a horror movie, over time, you realize, oh, I can survive this. Like it's not going to break me down, I'm not going to be completely overwhelmed and destroyed by terror, like I can actually go through this. And I mean, even you can pick up some things when you look at the lead characters who arise as being victorious in terms of survival.

Dr. Joy: Have you used any horror movies in your work for something like flooding or know of any cases of where that has been used?

Dr. Holmes: Let's see. I haven't used it for flooding explicitly, but I definitely have worked with patients who are trauma survivors and also are big horror movie fans, or even people who suffer from anxiety and are horror movie fans around it, and being able to draw parallels and kind of be like, what would Laurie Strode do in this situation? Or, you know, remember when this character did this and like how they confronted that. Especially if these are people who identify with those characters and really love the genre, then they can go like, oh yeah, I could do that. Or I can understand how I could navigate around this situation and be the final girl to be able to overcome all of this horrible stuff that I've gone through.

Dr. Joy: What are some of the common themes that you've seen come up in either black-created or black leads in horror films?

Dr. Holmes: Ooh, this is interesting because I feel like this is like a renaissance that we're in when it comes to black horror that I haven't seen before. Because the old trope is we don't last that long. It's like, “Oh, this is the black character that you're introducing in the horror film? Well, don't get emotionally attached because like they're not going to make it to the end.” But I feel like common themes when I think of a movie like Get Out or when I think of the wonderful show Lovecraft Country (which I'm so disappointed that's not coming for a second season but like it was brilliant) is of being able to confront the real-life horror of racism head on in a way that I haven't really seen in other films. There have been other films where if there were black lead characters or other characters of color, that they kind of alluded to it but they didn't necessarily make racism and white supremacy the monster. Which I think is like really interesting when it comes to the latest bit of black horror that we see.

But also, I think, when I think of those films like Get Out or when I think of a show like Lovecraft Country is how they're approaching trauma in a very complex way. There's race-based trauma that the characters are immersed in, which is like on a larger societal level. But then they also look at the individualized experiences of trauma, whether that be traumatic loss and grief from death, whether that be from facing psychological abuse and physical abuse as children, whether that be facing neglect or sexual harassment and sexual assault. But also, in terms of being able to look at the intergenerational transmission of trauma which you see on display when it comes to the Freeman family in particular in Lovecraft Country. And so those are some of the common themes I'm looking at.

But I think also one of the themes I see, I don't know if other people see it this way, but of seeing that we can survive. Which is, I think, a beautiful flip in terms of seeing black people in horror because... Especially if you're seeing people face like racism or white supremacy, even if it's in a supernatural context or a kind of alternate amplified context than what you would see in real life. It is refreshing and also, I think, hopeful to see like, oh, there can be black characters in this film that go through all this horrible stuff and they actually make it and they actually subdue or overcome the monsters in the film. Which I think is great.

Dr. Joy: Yeah, you know, you’ve raised some really interesting points. Because I do think that there is that angle that, oh, even if it's a fantasy, like we can overcome this white supremacy and this evil piece. But I think that there's also an angle of looking at that as like retraumatizing for people. And I've heard people talk about, oh, I just don't know if I want to watch that because it feels very triggering. Can you share just any thoughts about like what that looks like? And also, some tips maybe for how we can process these experiences in horror that might feel triggering.

Dr. Holmes: That's a really good point because I've heard, especially around Lovecraft Country, of people who've talked about trauma porn and do we really need to make more pieces of media that center black pain? And to what end? And I think it's complicated because I think if you are a black audience member, it's hard to withstand that. And I'm not gonna lie, like with both Get Out and Lovecraft Country, I had to pause multiple times.

For me, I think the reason why it's like going back to what you were saying earlier in the conversation. I can watch Mike Myers and know that's not real, like there's a certain degree of distance. But when I'm watching a show like Lovecraft Country, even though I know that there aren't going to be like Lovecraftian monsters in my real life, there are people like Officer Lancaster or Christina Braithwhite–I was like I know those people. Or like people like the Armitages, I've met people like that. And so it's hard because you don't have that safety net of, oh, this is just a movie. It's like it is, but it's not.

And I think if you're a black person who's watching these pieces of horror media and you find yourself being triggered, I think it's important to pace yourself, essentially. So if you're getting to that point where you’re like this is too overwhelming or this is too triggering, there is no obligation for you to have to participate in it. Or you can also wait to participate in it when you're in a good state. Because I think sometimes, as black people, we feel like we always have to just like show up and be about it when it comes to anything that involves our struggle.

And it's this weird conflict because on the one hand it's like we have to be involved because it concerns us, but then also it's so painful and exhausting to go through over and over again without any clear end in sight. And so I think it's important to just pace yourself. If you know you're not in a state of mind to like be a part of this media, you can wait or you can put it on the shelf until you're in a good space. Also, you can pace yourself. There is no shame in pressing the pause button and going through there.

I also do think being able to dialogue with other people about it–to like break down scenes and their meaning. You could do that with a therapist. If you get to that point where like it really is triggering and kind of reminding me my own race-based trauma or other traumas in my life, then definitely that's the appropriate place to do it. But you can even do it with like friends of the genre, like people who are also into it. Or even like listening to analyses from other people. I think like when we're able to process and talk about the things that trigger us or are traumatizing, that it helps us to make sense of it, which creates a pathway for us to be able to process it, work through it, and heal from it.

Dr. Joy: Thank you for that. I think that that's so incredibly helpful. And I did hear a lot of people saying like, okay, I had to like watch this not live, I needed to give myself sometime between episodes, so I think a lot of people were already practicing that.

I'm also wondering if you have ideas about how you can tell these kinds of stories responsibly. Some of the genre kind of calls for like scaring you and taking some of those shots, but I think when you are dealing with topics like racism and white supremacy, I think that you do need to kind of be gentle and like approach those topics with care. Do you have some thoughts about how those stories can be told... respectfully, I think?

Dr. Holmes: It's interesting because I was thinking about that. Like I don't think that they should stop telling these stories the way that they have because I do think that they're educational. Particularly for people outside of the black community who have no idea and who maybe, like for the first time, they were introduced to like the Emmett Till nightmare of what actually happened and being able to go like, oh, my god. Or being able to be introduced to like the history of redlining and segregation in Chicago in the 1950s and they didn't know about that.

So on the one hand, I'm like, I think it's important for nonwhite people to see the full brutality of it. Because there is a risk of people just kind of being like, if we tell these like very nice or kind of sanitized versions of our history, there's a risk of people outside of our community being like, I don't understand why you're so upset. Like it wasn't that bad, you know, based on all of these media depictions of how things were.

But I do think that to offset it, it would be nice and it would be interesting to see more stories in horror that incorporated black characters and used them as like three dimensional figures. Where it's like, yes, we do talk about race and racism but that's not like the centerpiece of that person and their story, it's a part of it. I would love to see like a black Laurie Strode. Like it wasn't until recently, I read an article... And I forget the name of the author and where it was published, but where the author of this article noted that Jada Pinkett Smith was like the first black final girl in a major horror film when she was in Tales from the Crypt: Demon Knight, which I remember watching as a kid. And I was like, oh my god, that's right. Because I was searching my brain, like what other major franchise had like a black final girl?

And I think that is a beautiful template for how like, oh, we can have a lead black character that's three dimensional, and you can look at and root for and want to survive this whole thing that everybody else is, you know, being failed to. So I think it's about balance as opposed to just being like let's stop telling these really intense stories of race-based trauma. We need to have it for people who don't understand but then also like, you know, for people in the community, let's have our nice like popcorn fun films where we watch the Rachael Trues and Jada Pinkett Smiths of the world make it to the end. And, yeah, shout out to Rachel True because I loved her character in The Craft.

Dr. Joy: You bring up a really interesting point and I think that this is the answer to so much that we struggle with in the black community. Is that there haven't been a lot of spots and a lot of resources afforded to us to kind of tell a spectrum of stories, and so it does feel like right now there has been maybe a heavy leaning on race-based trauma and those kinds of things. But with more time, we do get just your run of the mill kind of horror, where that lead just happened to be black as opposed to it being as much of a race conversation.

Dr. Holmes: Yeah, definitely. I think that there is a spectrum because I notice a lot of people kind of are engaging in what would be called (I guess) dichotomous thinking, where people are kind of like it's either or. You can either do this or you could do that. Like you can either engage in this like wonderful, happy go lucky version of the black experience and that's all, or you can go into this like more nuanced experience that goes into the trauma and the pain and the suffering.

But I think there's room for all of it. I don't think we have to kind of go back and forth between being like either we tell the horror of it and that's it, or we just tell this very sanitized cleaned up version and that’s it. I think there's room for varying degrees of our story. And pretty much when we talk about these conversations about representation in media, that's what we're talking about. We want, as black people, to fully be represented in all that we are as opposed to this kind of caricatured or stereotyped portrayals that we've been fighting against in media.

Dr. Joy: More for my conversation with Dr. Holmes after the break.

[BREAK]

Dr. Joy: You mentioned in this one film where Jada was the final girl, we don't often see that, or at least historically we haven't. Can you say a little bit more about like where black women fit into the horror genre? Like what are the things we get to imagine and survive within the genre?

Dr. Holmes: Oh, goodness. If I think about the entire span of horror movies, particularly like mainstream horror movies–because I can imagine that there are going to be some people in your audience that will be like, well, what about Ganja & Hess? Or what about these other kind of historical landmarks in black horror movies, but that aren't really that common? But if we think about the mainstream franchises, either black women are not there or they are basically just fodder to be murdered along with the other characters.

But I think in these newer pieces of black horror media, what you're seeing in terms of survival are these characters. Particularly, I think about, again, Lovecraft Country. You think of a character like Leti who had to face being neglected by a mother as a child and then was put in an orphanage and God knows what she got to experience through that, and then was a civil rights activist and photographer, and it's just really, really tough. And I look at a character like her, and not to mention like she was (spoiler alert, just in case you haven't watched this, people) like being killed like at least twice, if I'm remembering correctly, and then resurrecting like Lazarus.

And I think learning from a character like her is that survival is possible. Which, I mean, it sounds like such a simple statement but when you see a black character like her go through all that she's gone through and still make it to the end in this story that blends elements of like reality but also this kind of horror fantasy or sci-fi elements into it–it's a big deal. It can make you feel like, well, if she can survive that, I can too.

And in particularly, I think about this one standout moment when Leti buys the Winthrop House in the north side of Chicago, which is like a predominantly white area of Chicago at the time, and is renting out rooms in this house to like other black people. She has this big celebratory party and they look out of the window and they see a white cross burning. And even before this, there were three young white men that parked their cars and put cement blocks to the steering wheel so the alarm and horn could be going on all hours of the day and night. And she's in this beautiful blue dress and high heels and she gets a bat and she goes out and she just knocks all of it out and I was like, “I want to be you.” Because he was just so strong and powerful in that moment.

Again, like one of the reasons why I loved the show is that it presented a nuanced portrayal of black life, black people, but also black people dealing with trauma, that wasn't neat and tidy. Like these were complicated characters. In fact, a number of these characters not only were victims of trauma or not only victims of oppression, but also enacted oppression in a number of ways. And so I think that that was good in terms of being like there aren't clear villains and heroes. There are some people that like weigh more heavily on either side, but you can't say like, oh, this is a completely innocent character or this is a completely awful character and you don't know.

And I think it's also good to like be able to have the backstory of people, where it's like even if you don't want to justify the actions of someone like Ruby. Or even if someone like Montrose, to be able to see their backstory and go, “Okay, I can understand why you got to this place. Like you're not a monster. It's just this is the best that you could do in this situation that you've been thrown into,” I think was really good.

Dr. Joy: Yeah. You've referenced a couple of times like who gets to make it to the end and so it feels like that is a highlight of the genre, like who survives the horror. What stories do we tell ourselves about who makes it to the end?

Dr. Holmes: Yeah, this is a big thing. Especially when we look at like the traditional analysis of the final girl, she's usually been white, middle class, someone who is pure in terms of she hasn't had sex, she doesn't smoke or drink, so like someone who's very morally upright. And how these are the things that, whether she acknowledges or not, that have allowed her to be able to make it to the end. Which excludes a lot of people, when you think about it. And it's weird because it's like that analysis can be empowering for some people–because like traditionally, women in general are not seen as being strong, or like that's the stereotype. And so to see a woman make it to the end, not only because of the strengths that she displays (psychological, emotional, and physical strength) but also because she is able to use her wits.

Because a lot of the final girls, traditionally, they're not winning because like they're coming and being like, I'm super tough and I'm gonna kick your butt. They're coming in with like, I'm clear-headed, I know the threat that I'm facing and I'm going to figure it out. And so they're able to see the things that other people can't see because they're so distracted or they're in denial or they think that making foolish decisions like running towards the cemetery when you should be running towards the car, is gonna somehow save them.

But I think the stories that we say to ourselves, particularly in the context of being black women and femmes dealing with horror, either real life or in the genre, is sometimes we may lose hope. That like, oh, I couldn't possibly win because this context or this world wasn't designed for me to win, like it's already been set up for me to lose. But when I think about like the real-life horror show that is racism, we have so many historical examples of people who’ve won and who were able to make it to the end and who were able to use their suffering and their pain to advance liberation and rights for themselves and others.

So like looking at people who are referenced in Lovecraft Country in terms of black women and femmes, you’ve got Josephine Baker who people sometimes... I don't know if people understand like how remarkable this woman was, of not only being able to escape racism in the United States and be able to have this illustrious career, but also was a French resistance fighter during World War II. Hid Jews in her mansion from the Nazis when the Nazis occupied Paris and France as a whole, also was a civil rights activist, was openly queer, particularly bisexual. And so I was like, she's remarkable. If you look at someone like Bessie Stringfield who crisscrossed the United States of America multiple times as a black woman motorcyclist.

And so, even when we think about the mother of Emmett Till who I think that woman is a superhero for what she did. In the midst of her grief to be able to showcase the real-life horror that (at that time) people were still kind of in denial of–the brutality of racism and how it was ripping people, including young innocent children, apart. So I think that it was remarkable because I can't imagine being in that mindset, having to deal with what she dealt with and to still be able to be like I'm going to show people what happened. And I'm going to use this to be like even though my son is dead, other children, other people don't have to die. Hopefully, if people can like really look and have some kind of human feeling and compassion and realize how just disgusting this is.

That even though we can often get these messages or tell ourselves and internalize these messages that like this world is not designed for you, you have to work twice as hard and still not really get what you deserve, there also are plenty of examples of people who, through all of this adversity have been able to succeed and not only advance themselves, but help advance all peoples that fall under the umbrella of the African diaspora.

Dr. Joy: I do want to, though, go back to this conversation about black women in horror because I feel like we have a major feat coming up this summer. I don't know if Nia is the first but Nia DaCosta is directing the reimagining of Candyman. I know, right! And so I feel like this may be one of the first instances of a black woman actually being at the helm of a horror movie this big. I'm wondering, through a black woman's lens, what we might expect or how you think that might impact the retelling of the story.

Dr. Holmes: This is interesting because I've watched the trailer. I watched the original Candyman and loved it and then I watched the trailer and have gotten like as much news as I can about where they're reimagining the story. Which I think it's interesting where it's like Candyman in the original film adaptation (because it's based off of a Clive Barker story) is basically a victim of a racist white vigilante mob that's torturing him for committing the great sin of having romantic and sexual relationship with a white woman, and it's shot in Chicago.

But then with this reimagining, it's looking at Candyman as being a very clear-cut villain. Where it's like from the beginning, he comes through as being this child predator and murderer and almost reminding you of like Freddy Krueger kind of. And then how it's kind of like his specter, or his spirit or his energy is still poisoning the community. And I think it's interesting because it's making me think about through that lens of looking at how pain and oppression can be internalized and can attack other people that are innocent.

Because when you look at Candyman, both in the original film adaptation and what's being reimagined here, it’s like this is somebody who's turning against members of his own community for no good reason. And kind of looking at those elements of how sometimes within the black community, we can have people who turn their pain outwards, who instead of being able to process it in constructive ways and adaptive ways and to fully heal from it, turn it outward and attack innocent people. And so that's what I'm looking at, of like her delving deeper into this, of like how this unresolved pain and suffering can bleed out and continue to just have these ripple effects, generation after generation, in one particular community.

Also looking at the kind of stories we tell ourselves about these kinds of legends and things, about like what happens. Because I think the setup is like there's this artist that's like trying to bring this back in an almost kind of like selfish manner. Because it's like, why are you revisiting this painful event and trauma and like resurrecting it in this community that struggled? What's supposed to come out of it? Like what's the endgame here? Are you just doing it because you're like, oh, I think it's gonna be cool, the idea for an art show. But have you considered the ramifications for the people who lived through that?

Which is something that's been a big conversation in multiple areas of media. Of like, if we're going to cover something that was a real-life tragedy, particularly when we look at something like True Crime which has like gone off like a rocket, of there are lots of people who are like we need to focus on the victims, not on the people who perpetrated the acts of crime or trauma. Because what inadvertently happens is you make them into these antiheroes and people focus way more on them as opposed to like the people that were hurt and sometimes this is done without the permission of survivors or their families and loved ones. And so it brings into question, for me, like that lens of like, okay, at what cost are you bringing up this old stuff that's like, really painful?

Because one of the things when we look at adversity or events of extreme stress or tragedy, is sometimes people are like, well, if the event ended, then why are people so upset still about it? If it's done, it's done. But it's like that's not the way these things work, is that there can be this long haul or shadow that's cast after something happens that affects people psychologically. And I kind of make the comparison of like, let's say you broke your leg. Even after going through physical therapy and surgery and having it reset, it's like there's still going to be a lasting impact of you maybe having a different kind of gait. Maybe having a certain level of pain when you do certain activities and you know it's because of this particular incident. And so even though the incident is over, the consequences of what's done to you haven't ended and it's the same thing when it comes to the things that injure us psychologically.

Dr. Joy: That’s so incredibly powerful. More from my conversation with Dr. Holmes after the break.

[BREAK]

Dr. Joy: I would love for you, Dr. Holmes, if you can... I think there are some movies you go into, like you've just made the distinction for yourself. Like, okay, I stay away from this entire class of things because that feels like too much. And I think some people may not know what they're getting into, so I would love it if you could maybe offer some tips for people who maybe do find themselves triggered by a horror movie or didn't know what they were getting themselves into and they need to take care of themselves afterwards. Do you have some strategies for maybe how to like process what they’ve experienced through a movie?

Dr. Holmes: One thing that comes to mind immediately is like prevention, so being able to do your due diligence and research before you go into a movie. I know that we are living in this time where a lot of people are like I don't want it to be spoiled. I'm not one of those people that gets that bothered by spoilers, it's like it's not going to ruin the entire film for me. In fact, I'm the kind of person where I like getting some information in advance. That way, I know this is something I can handle as opposed to just going in and being like, oh, this is too horrible.

Like The Human Centipede, which is kind of like an infamous horror film that I won't describe because it's just blah. But it's one of those films that like when I found out about it, I was like no, thank you, I won’t take part in any of that. But if you're one of those people where it's like, oh, I just popped this or I went to the movie theater or I like checked out something on Netflix and I was completely caught off guard, is of taking time to kind of like process it.

So you can journal out your thoughts and feelings about what's happening. Again, you can also talk to somebody that you know would be a safe understanding person to be able to get your thoughts and feelings. Particularly, pinpoint what about it has upset you. So like it's more than just usually if people find themselves being triggered of like, “oh, it was scary,” because lots of things are scary. But it's like what in particular about this film was triggering to you? Was it something that the person said? Was it that this person resembled somebody in your real life that did something horrific? Was there something in the storyline that really affected you because it reminds you something that you or a loved one has been through?

But then also, I think, in addition to kind of like processing and pinpointing those things, being able to take some time away from horror if you need to. Or also kind of like what I've done of like understanding what elements within the horror sub-genre are for you and are not, so that you don't necessarily feel like I have to love everything. Because you can still be a big fan of the horror genre and still get a lot of meaning and nuance out of it without watching every single film and television associated with it that's ever been produced. I think being able to know what your limits are with that.

Other things that help people. Also, just basic kind of self-soothing skills–diaphragmatic breathing, relaxation, grounding, meditation–so that you can kind of get back into your body. Because sometimes when people find themselves in this state where they watch media, there can be sometimes where people are like I had nightmares or there are things about the film that I'm seeing in my real day to day life that are triggering. And so it's like, okay, if that's the case, of being able to use things to like soothe your body. That way, you can be able to be grounded. And I think it also can help you in terms of distinguishing between the scary thing that you saw in film versus what you're encountering in your day to day life. That way, you can resume feeling safe. And also being able to, again, make that distinction between what's a real danger that has appeared in film and then what is happening in your real life, essentially.

Dr. Joy: Thank you so much for those. One final thing, I want to go back to the point that we made earlier, just around especially you described it as a renaissance, where you feel like more black-led stories are being told. And we found an article that talked about the fact that the reason why, historically at least, it's been difficult for filmmakers to kind of include or make black people more a part of the genre, is because the things that terrify black people at our core and the things that terrify white people are like vastly different.

And so for us, we've already talked about like for black people, the horror comes from living in a world where you know because of your skin color you're not accepted. And like things could go awry at any moment. Have you seen that? Are there thoughts you have about that kind of an idea?

Dr. Holmes: I definitely think that's pretty on the money. Because usually, when we're talking about film in general, they try to historically make it to the broadest market. And that usually means we're going to cater to people who are considered to be privileged or dominant in our society, which includes white people. And so they're not going to consider what's like really horrifying to other folks. And even not just with black people, but other people that belong to marginalized and oppressed groups, because I think about with The Stepford Wives of, you know, that was an early element of like social horror.

Or even if you want to go into something like Rosemary's Baby, of being able to talk about this idea of living in society as a woman where you don't have agency over your body and where you're viewed as nothing but an object. Like that's horrifying, and being able to inject that into the horror genre. When I think about horror and when I think about the things that have terrified me, but especially when it comes to something like evil, of I've never been terrified of supernatural things. Any time I felt like I was in the presence of like pure evil, it's been other human beings in my life.

And so it's been around those things like racism, misogyny, misogynoir, it's been around various acts of trauma, it's been around bullying and harassment, it's been about biphobia and sexism and all of those things. And also, like looking traditionally throughout the history of film, usually it's like white sis, heterosexual men, that have been at the helm of funding these films and everything. And so I think if you don't have people who have a different lived experience at the table to go, “Hey, this is actually a worthwhile idea that you haven't considered yet–why don't we explore it and try it out?” It's just not going to come to screen.

And I think we've had those ebbs and flows, starting in, I want to say maybe like the latter part of the 20th century and then really moving forward, where there's been more opportunities. Both from like indie filmmakers and mainstream filmmakers, to bring these stories to light. But I think that that's pretty much the explanation, is just if you don't really have to deal with like racism, it's going to be hard to see how terrifying it is.

Dr. Joy: Right. What are you excited about or what are you looking forward to, maybe that doesn't exist in the genre now, but that you'd love to see?

Dr. Holmes: Oh, wow! I feel like my dreams are starting to come true in terms of the genre, of just seeing like more queer people and also people of color being centered as the lead characters that we root for and who are being given like these three-dimensional character arcs. Like there's one series of films I haven't watched yet, but like Fear Street that's streaming now that I'm really excited about. There's also been some really interesting films with female directors around like gender identity and the horror connected to that.

And so I think I want to see more black final girls and boys, and everyone in between on the gender spectrum being able to go through this and make it to the end and be the ones that we follow. Even though we've had examples of that like with the penultimate Night of the Living Dead, with the lead character who was black but unfortunately didn't make it to the end. But, you know, I want something that has that kind of spirit where it's like, oh, this is a fully-formed character that not only black members of the audience but other people can identify with. And doesn't forsake their blackness. Because I think sometimes there's that tug of war between, okay, we have this relatable character but they kind of are watered down or like they don't even acknowledge race or anything like that. They just are this blank slate and so that one character that fully knows like all aspects of who they are, including their racial identity, but at the same time, everybody could go like, I love this character, I feel like invested in them and I want to see them make it out alive. I mean, I will follow them.

Also, just in general, not just with horror films but in general, I'm wanting to see more original stories come out. I think this is why I had a bit of a heartbreak with Misha Green not being greenlit for a second season. I think she's a brilliant storyteller–and for our audience, she was the showrunner for Lovecraft Country. And I just want there to be room for her and other storytellers like her to make new stories because I'm really tired of seeing reboots and remakes and prequels of preexisting properties. Because I think that there are a generation of wonderful directors and screenwriters who have amazing stories and ideas.

And we should, not just we as audience members... Which I think, honestly, there's a lot of audience support and craving for this, but I think that both audience members as well as like the studio heads that are responsible for greenlighting these pictures should take a chance. Take a risk of like just putting more interesting things out there so that we can have this new bulk of films to go off of instead of remaking the same franchise for the umpteenth time. I think there are some things where it's like leave it alone. Even if it's imperfect, it's fine the way it is.

Dr. Joy: Right. Well, Misha just signed a deal with Apple so we will stay tuned to see what new things we might be getting from her. Thank you so much, Dr. Holmes. Please let us know where we can keep up with you. Would you please share your website as well as any social media handles you'd like to share?

Dr. Holmes: I am on Therapy for Black Girls directory. I'm also on InclusiveTherapyWellness.com/ lana. And you can also find me at www.Facebook.com/OnwardTherapy, which is the practice I'm a part of, Onward and Outward Centre for Inclusive Therapy and Wellness. Those are, I think, like the three main places you can catch me.

Dr. Joy: Perfect. Thank you so much for all this information, very, very interesting. I appreciate you, Dr. Holmes.

Dr. Holmes: You’re welcome. Thank you for this opportunity to share this with you and your audience. It's been lovely.

Dr. Joy: Thank you.

I'm so glad that Dr. Holmes was able to share her expertise with us today. To learn more about her and her work, be sure to visit the show notes at TherapyForBlackGirls.com/222. And don't forget to text two of your girls and tell them to check out the episode as well.

If you're looking for a therapist in your area, be sure to check out our therapist directory at TherapyForBlackGirls.com/directory.

And if you want to continue digging into this topic or just be in community with other sisters, come on over and join us in the Sister Circle. It's our cozy corner of the internet designed just for black women. You can join us at Community.TherapyForBlackGirls.com. Thank y’all so much for joining me again this week. I look forward to continuing this conversation with you all real soon. Take good care.