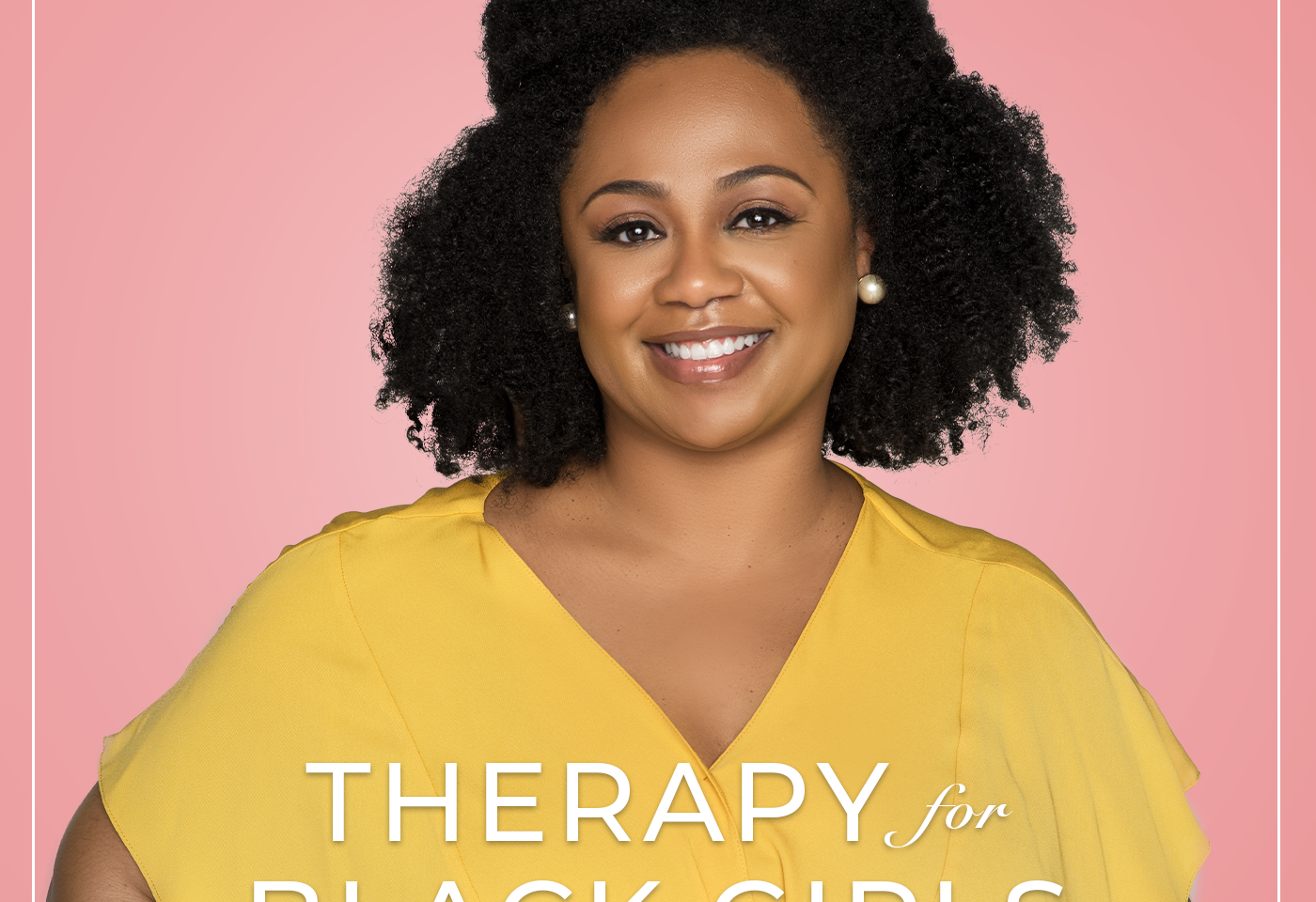

The Therapy for Black Girls Podcast is a weekly conversation with Dr. Joy Harden Bradford, a licensed Psychologist in Atlanta, Georgia, about all things mental health, personal development, and all the small decisions we can make to become the best possible versions of ourselves.

There are multiple layers to unpack when discussing Black women and girls who die by suicide. Historically much of the research conducted around suicide has been synonymous with whiteness, although Black women harming themselves is not a new phenomenon. As death by suicide has continued to rise among Black women and girls in recent years, pointed research in this area is still sorely lacking. This week we’re joined by Dr. Jeannette Wade and Dr. Michelle Vance, Assistant Professors at North Carolina A&T State University, whose work centers suicide research & intervention among Black women and girls. In this conversation, we explored psychological stressors like sexism and racism that can lead to suicidal ideation, how research efforts conducted by and for Black women can save lives, and the importance of humanizing Black women with mental health issues.

Resources

Visit our Amazon Store for all the books mentioned on the podcast!

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline

Helping Someone Who May Be Suicidal

Support Groups for Those Who’ve Lost Loved Ones to Suicide

Where to Find Dr. Wade

Where to Find Dr. Vance

Stay Connected

Is there a topic you’d like covered on the podcast? Submit it at therapyforblackgirls.com/mailbox.

If you’re looking for a therapist in your area, check out the directory at https://www.therapyforblackgirls.com/directory.

Take the info from the podcast to the next level by joining us in the Therapy for Black Girls Sister Circle community.therapyforblackgirls.com

Grab your copy of our guided affirmation and other TBG Merch at therapyforblackgirls.com/shop.

The hashtag for the podcast is #TBGinSession.

Make sure to follow us on social media:

Twitter: @therapy4bgirls

Instagram: @therapyforblackgirls

Facebook: @therapyforblackgirls

Our Production Team

Executive Producers: Dennison Bradford & Maya Cole Howard

Producers: Fredia Lucas & Cindy Okereke

Assistant Producer: Ellice Ellis

Session 249: What's Missing From the Conversation About Black Women & Suicide

Dr. Joy: Hey, y'all! Thanks so much for joining me for Session 249 of the Therapy for Black Girls podcast. We'll get right into the episode after a word from our sponsors.

[SPONSORS’ MESSAGES]

Dr. Joy: There are multiple layers to unpack when discussing black women and girls who died by suicide. Historically, much of the research conducted around suicide has been synonymous with whiteness although black women harming themselves is not a new phenomenon. As death by suicide has continued to rise in populations of black women and girls in recent years, research in suicide prevention and intervention amongst our community remains necessary. This week, I'm joined by Dr. Jeannette Wade and Dr. Michelle Vance, assistant professors at North Carolina A&T State University. The duo centers their work on suicide research and intervention among black women and girls.

Our conversation explored psychological stressors like sexism and racism that can lead to suicidal ideation, how research efforts conducted by and for black women can save lives, and the importance of humanizing black women with mental health issues. If something resonates with you while enjoying our conversation, please share it with us on social media using the hashtag #TBGinSession or join us over in the Sister Circle to talk more in depth about the episode. You can join us at Community.TherapyForBlackGirls.com. Here's our conversation.

Dr. Joy: I'm really excited to dig in with both of you, and again, thank y’all so much for joining us. I would love it if we could just start by each of you telling me a little bit about how did you come to this work, and can you tell us a little bit about your research? If you'd start, Dr. Vance.

Dr. Vance: When I was in my doc program at the University of Central Florida, I worked on a national suicide prevention initiative and it was called The Florida Link–Florida linking individuals needing care. I was basically the care coordinator liaison between the mental health agencies and the university researchers. Basically, what this was was a care coordination model for youth who were hospitalized in an inpatient psychiatric facility but then, after discharge, it was a program that worked with them for 90 days.

This was the focus of my dissertation. However, I chose to use only the black and brown girls who were discharged from the psychiatric inpatient facilities for the care coordination model because I specifically wanted to look at if there were decreases in suicidality as well as decreases in depression across the 90 days. And also, were they able to stay engaged in services? And so that's how my research really in suicidality started. I've always done a lot of work around mental health and mental health disparities, but it really was my dissertation in my doc program that got me involved on more of a practice and research level.

Dr. Joy: Thank you for that. And what about you, Dr. Wade?

Dr. Wade: Well, I'm a sociologist, I'm trained in gender and medical sociology. When I was doing my doctoral research, I looked at black men and women and white men and women during emerging adulthood (which is 18 to 25) and I was interested in the ways that gender contributes to engagement in health risk behaviors. I looked at fast food consumption, sexual risk behaviors, and binge drinking. And through my research, I noticed what the most unexpected finding was– black women actually... when we measure gender in the traditional white way using the Bem Sex-Role Inventory, black women come out as the most masculine. And we already knew that masculinity was tied to health risk behavior but we hadn't focused on black women because we always associated masculinity with manhood.

I sort of left all the other groups behind and just focused on black women because I was very fascinated by the idea of black women being masculine. And I myself am a black woman and I'm a wife, I'm a mom, but I'm also ex-military. I also have a PhD, so I understand how masculinity could be conflated with the way black women do gender, which we call strong black woman. So I've really been getting into this strong black woman idea and how it contributes to health risk. Because as we know, wearing so many hats, doing it all, being feminine and masculine, being leaders, all of that is stressful and stress requires coping. Unfortunately, a lot of us have unhealthy coping behaviors.

Actually, a mutual colleague of ours, Dr. Sharon Parker, brought Dr. Vance to me one day and she said, hey, she's the new kid in town at our university and I think you two should collaborate. She's interested in suicide risk among black girls and women, and you do such an excellent job contextualizing these health risk behaviors, I think you two should collaborate. So she has the social work background, she understands the clinical side, and by me being a sociologist, I can help understand how aspects of black womanhood might put you at risk.

Dr. Joy: Got it. Yeah, so I read the piece that you both were quoted in for Time, a couple of weeks ago, and knew that I wanted to sit down with you all because I think that there are just so many layers to unpack. We think about and talk about suicide as it relates to black women and girls, and so I would love to hear a little bit more about maybe what your research has found and what other research has found related to the risks. In particular, for black women and girls as it relates to suicide.

Dr. Vance: I'll definitely start with that. One of the things that we're really looking at, and specifically in prevention as well as intervention, which is why I chose to focus on the black and brown girls because most of research has been synonymous with whiteness. And a lot of the research that we've looked at has been research with non “persons-of-color” and non-black communities specifically. What we're noticing is that we're seeing this increase in death, we're seeing this increase in suicide related behaviors. We know that black people did not just start harming themselves or dying by suicide but we've never specifically looked at how young black girls and young black women are experiencing the risk factors that are already studied in the literature.

Like if we talk about mental health symptoms and we specifically talk about anxiety and depression, then we can go back and look at literature about what are things in our lives that cause anxiety and depression. But it could externalize and be internalized very differently based on our identities and we all identify differently. So if we're talking specifically about black girls and black women, this is why I think the work that Dr. Wade and I do is so important. Because we want to look at the intersecting identities, but also how do those psychosocial aspects of those intersecting identities put black girls and black women at risk?

I know that between 2000 and 2017 (I believe), there was 182% increase in suicide deaths for black girls and black young women, ages 10 to 24. I think that tells us, developmentally, there are some things we need to look at, where I think the health behaviors come in as well. I also think that we need to look at these specific risk factors. And then how do those protective factors maybe help or do not help, based on the fact that we're living in a society that still is saying, “Oh, my goodness, these black women in public image are dying by suicide, why?” Well, first you need to identify that they're human and that we do see that there's things that we're not looking at because we've not been trained to look through any other lens but whiteness.

Dr. Joy: What would you add there, Dr. Wade?

Dr. Wade: Interestingly, like Dr. Vance said, historically, we didn't think about black women when we thought about suicide so there are actually three paradoxes that exist in the literature. One is the gender paradox which says men are more likely to commit suicide. One is the race paradox which says whites are more likely to die by suicide. And then there's even an African American woman's paradox that talks about the way we use our spirituality and our sisterhoods to protect ourselves from dying by suicide. Really, this recent shift in the trend is not studied well yet so I think there's going to be a lot of new literature emerging. But up to now, a lot of studies of black women and suicide actually looked at the protective factors because it never made sense that this group that faces race and gender oppression has low rates. I think that's what's been more fascinating historically. Now we are shifting to sort of look at what's causing this new spike.

Dr. Joy: You know, that's a really interesting point you bring up Dr. Wade because, historically, it's a misconception but I think that there was some truth to it. That black women and black girls did have the lower numbers in terms of suicide historically. But now, as you’ve mentioned, Dr. Vance, there’s been this huge increase. We know that stressors have increased, racism has not stopped at all, but are there other things that you can point to that have led to this increase that we've seen that is different from what we've seen historically?

Dr. Wade: Well, this is just an interesting sort of tidbit. I just watched a special where they had men having a dialogue about suicide. One man talked about suicide rates are the clearest indication that men have it harder in society–because if they didn't, why would they die at such high rates when it comes to suicide? And I just thought about how counterintuitive that is and how the suicide rates really spoke to how men are ill prepared to face adversity and black women are so prepared to face adversity. We're basically told as children to expect adversity all the time and move on, and be strong, and go to church and get through it.

He talked about men have such high rates because they head households, they're financially in charge of society. If anything goes wrong, it falls on men. And that is sort of the shift with black women. Because we've always faced racism, sexism, we've always had to work hard. We didn't have that same feminist movement where we were fighting for that right to work, we've been working since slavery. However, the power is what's new. And when you look at women in these high-power situations that are almost similar to the white men who are more likely to die by suicide, they were in powerful situations.

I think, although we prepare black girls for some level of adversity all the time, being powerful, highly educated, highly successful in spaces comes with a huge layer of gendered racism that can really take over you. I'm sure you can relate, as a highly educated black woman, you find yourself succumbing to microaggressions constantly. The research shows black people with more education and income and better careers actually face more microaggressions when it comes to racism than black people who live in predominantly black communities who face more structural racism on a daily. I think no black person can educate or income their self out of being black in America–there's gonna be racism, there's gonna be sexism–and then when you add that layer of power, I think that's what might be a big piece of this new trend. Dr. Vance and I, we created a model which is theoretical, but we're actually in the process of testing it. Soon, be on the lookout for our next article where we actually test the model and plug in all these psychosocial factors to see how they relate to suicide risk.

Dr. Joy: Thank you for that. We'll definitely be on the lookout for that. Did you have something to add there, Dr. Vance?

Dr. Vance: I was just really thinking also, because Dr. Wade you had mentioned, if we think about black women in all settings. And I think that's the important part, is that if we're now paying attention to psychological stressors as a result of experiencing sexism and racism, we need to look across settings. I know I've had a lot of really great conversations with black women and their experiences in medical settings. Like most people wouldn't think... When you have privilege, you wouldn't think that you're going into a doctor or you're going somewhere where someone is supposed to be treating you or helping you with things, but you're experiencing those microaggressions in every setting of your life. And I think that we're getting to a point that people, and specifically black women, are being more vocal about the experiences that they're having in a lot of different domains.

I think that one of the things that I hope that we're going to also do with our model is really get to... and even hopefully create a scale, Dr. Wade, that catches how women feel and what they're experiencing and what they're going through in all of these different settings. Because it gets me to thinking about why would someone say that they may be experiencing levels of depression or anxiety or psychological stress that is taking them out of their normal character? Like when is it that we can't cope with the things that we're normally coping with? I really do believe that there is some socio historical stuff that is just present today that we're just not tapping into, in a lot of ways. From a research perspective. And if research guides what we do in practice, and our research has not looked at specifically the things that we need to look at for racialized and minoritized communities, then we're missing the mark totally.

Dr. Wade: And another elephant in the room I just want to throw in is social media–what’s different today versus yesterday. We know that black women that are in that same category (the very successful, educated) these are the people on social media all the time. It's well established that for women social media has a direct tie to self-esteem and that we come to compare ourselves to other people constantly. But then as a black woman, you have that other piece which is these viral videos of police brutality, these Karen videos. Just you name it, there's always a video circulating that is going to have a negative effect on your mental health. It's like, do I want to be a perfect woman? Or how do I navigate my blackness in this racist society? “I'm so angry.” I think we can't leave out social media either when we talk about what's different and why would it be uniquely hard for a black woman. Because social media has racism and sexism on a plate for you.

Dr. Joy: You know, as you all were talking, I think somebody earlier mentioned there are some traditional risk factors that we are trained in (in terms of being clinicians and as researchers) to kind of look for in terms of risk factors for suicide. So if you've had a friend or a family member who's died by suicide, if you have access to the weapons that can increase the risk. But you mentioned that some of these risk factors might not actually look the same for black girls and women. Can you talk a little bit about maybe some of the risk factors that may be an indicator that might lead to suicidal ideation or execution, that we may want to be on the lookout for?

Dr. Vance: That's a great question. I know one of the things that I was thinking about... I believe, Dr. Wade, we were talking about this as well. If Black women or black girls are experiencing puberty at a younger age, let's just say, that's what the research says. I don't do that research but that's what the research says. If black and brown girls are reaching puberty at an earlier age, then there's been some connection or talk about how they may be even engaging more in sexualized interactions or relationships at a younger age. And if that then happens, then is that increasing any risks of interpersonal violence? Any more risks of sexual abuse? How are those things, I think, even playing out? That's just one thing that I'm thinking about.

The other thing I think comes to just in general self-care. And so I know Dr. Wade talked a little bit about the strong black woman script and the Superwoman schema. I would like to talk a little bit more about that because some of the work that I've been doing is actually talking to parents about how do we start having these conversations and shifting narratives with our children? Around expressing feelings, identifying when it's okay to be vulnerable, showing that you may be sad, that you don't have to always prioritize others’ care over yours and I think there's a lot of generational stuff as well there. So I would like to have a little bit of discussion around that because I think that there may be some risk factors there that we need to tap into.

Dr. Wade: Just to be clear for everyone that's not familiar with the strong black woman idea. The personality traits that are associated with being a strong black woman are: you have to sort of give off this vibe that you're strong by nature; it's not something you're trying to be, you just can't help it; that you hide emotions; that you're resilient; you’re a caregiver; you always have solid mental health; you're religious; you love yourself; and you manage to be beautiful and feminine all at the same time. This is a unique risk factor for black women. It’s understudied in the context of suicide risk, so that's the direction we're headed in but Cheryl Giscombé out of UNC created the Superwoman schema, which is a way for clinicians to really measure how much black women subscribe to that strong black woman script. With the schema, she made strength be one piece of it and also measured how we suppress emotions and how resistant we are to depending on other people. So we are going to include that in our next study to really see for sure if being a strong black woman does create a risk for suicide. And then if so, I'm sure other scholars who study the Superwoman schema and strong black women will look into its relationship with suicide risk as well.

And then another thing that we're adding is gendered racism. Going back to intersectionality–which is the idea that you can't just talk about women, you can't just talk about black people, because every part of our identity shapes every encounter we have–for black women, it's gendered racism in particular. And in our first article, I used the arrest of Sandra Bland as an example, where if you listen to the dialogue between her and the officer, you can see a man who doesn't see a woman and you can see a woman who can't believe this man doesn't see her as a woman. Because he calls her names that are not associated with womanhood and then she asks him: Does that make you feel like a man? Do you feel tough talking to a woman that way? That's at the intersection of race and gender, where black women are not expected to receive courtesy, they don't receive chivalry, they are to speak when spoken to. If they get pulled over, smile and nod and do as told. Gendered racism, we actually have a question that says, “How often do you have negative experiences that are shaped by your gender, shaped by your race?” We're going to account for that as well because, obviously, that will be a unique risk for black women.

Dr. Joy: More from my conversation with Dr. Wade and Dr. Vance after the break.

[BREAK]

Dr. Joy: I want to go back a little bit, Dr. Vance, to your comments around like suicidal risk in adults versus children. Are there some things that we may be missing in terms of children? Like does suicidal risk or suicidal ideation look different in children than it might in adults?

Dr. Vance: Yeah. I would say absolutely that it looks different. And I think not only does it look different, I think us as the adults don't always even want to see it or know what to see it or start to call it something different, and then the babies then call this something different. And I think that's where I was going to earlier in talking a little bit about shifting narratives and generational things. I think that it's really important that we're able to help children identify what it is that they're feeling. And what does that look like? And how do we express sadness? How do we express anger?

One of the things, Dr. Joy, that we do notice, especially for black boys in particular, that they’re funneled through the juvenile justice system and so they're not even getting the treatment that they need. If we're seeing young black girls and young black boys exhibiting behaviors that were already externalizing that they're violent or they're angry or they don't know how to cope, I think we're missing those things. We need to look at our kids and look at how they're exhibiting whatever emotions that they're having, and be able to kind of talk with them and see that and listen to them. But I think that there's a lot of responsibility there on adults, not only as parents, but us as providers. Because if we look at a young lady who has just went into a classroom... I remember a viral video in a classroom, that she just starts slinging desks and slinging bookbags and screaming and “I want to leave” and all of these things. And I'm hearing even the teachers (who may not be trained or equipped to deal with those things) still treat her like it's a behavior issue, there's something that is preceding those behaviors.

I don't know that children know how to necessarily explain or express what it is and I don't know sometimes as adults that we do a better job with that either. I think with adults, we've had more time suppressing, masking, and hiding our normal emotions, things in our mental health that we all have. But kids, I think, are learning that at a younger age and so I think, and I don't know when, but there's got to be a time where we can get in and do some sort of intervention. To kind of go back to just make sure that I'm clearly answering your question, I do think that it presents differently between childhood and adulthood but I also think that it also has to do with how we identify it.

Dr. Joy: Can you both talk a little bit about what leads someone to being suicidal? Because I think that that is still the very difficult piece for people who maybe have not struggled with these kinds of mental health concerns. Is that there's some confusion about like, how does someone even get to a place where they want to end their own life? Can you talk about like what are some of the things that happen that may lead someone to feel suicidal?

Dr. Wade: So far, what we know for sure about black women, the three greatest risks are using drugs or alcohol, sense of hopelessness, and a past with sexual assault or violence. Obviously, we don't necessarily share those kinds of things about ourselves. But if there is someone who has a history with sexual assault or violence, and you see a drug or drinking habit that has gotten out of control, and you hear things like “I feel hopeless,” then those are red flags and that's when you should really be on alert, I would say.

Dr. Vance: I think another thing is Dr. Wade said something that brought me back to... Because you asked the question, what would bring somebody to that point? First of all, we know that it's generally not one thing that happens that gets somebody there. And if somebody is already in crisis, the risk is higher for a suicide attempt, for other suicide related behaviors. And so if we think about when intervention is probably best, if someone feels like “what could I have done at that moment?” maybe there isn't anything at that moment. But I think it goes back to if you know someone who has disclosed that they have struggled with depression, that they have seen a therapist before, that they have at one point been on medication but they continue to walk through life like they're fine or maybe that they don't need that...

I know we've read a lot about high functioning and the use of that term and we can come back to that if that's something you want to get into at another time. But I think at that point, that we have to stay contacted with people and ensure that they're tapping into the supports that they have. Because I sometimes think, like with anything else, when we're going through something and then we come out of it, we may forget that we maybe went through that. And something (and we may not know what it is) could trigger us and put us sort of back into that position. And then if we have to go all the way back to the beginning and think about how did we get through that the last time, I think that there's a window there that’s maybe hard for some of us to work through. And so I think there has to also be some things about how we destigmatize what are some of the things that we're feeling or what are some of the things that we're going through? And what does that support look like and what does that help look like?

Dr. Joy: Yeah, even to your earlier point, Dr. Wade, around how black women and girls are basically groomed and socialized to kind of expect adversity. And so then we do have maybe a sexual assault or something major happens but it doesn't (in our minds) maybe rise to a crisis level because we've always been thinking like, oh, this kind of thing happened to my aunties and my grandmothers. And so when we tell it to someone, then there's the reaction of “oh my gosh,” but internally maybe it doesn't trigger as something that is a real concern.

Dr. Wade: Yeah, and that goes back to the strong black woman idea of just always looking like you have solid mental health. We do things like eating, sleeping, high risk sexual practices, to cope with all this because it’s not like we take it on and we really are just made of sheet metal or something. It hurts so we do other things to deal with that pain. And that’s something else you can talk to people about. If you see people engaging in health risk behaviors at unhealthy rates, it’s not because they’re lazy, it’s not because something’s wrong with them, it’s not because they don’t have motivation. It’s generally something is bothering them. And so that’s also a red flag where you can make yourself available if you have the space in your heart.

This is a takeaway I got from one of my students. She said as we become strong black women, always ask the person if they have space before you start venting. Because I know like my girlfriends and I, if we call each other, “Girl, let me tell you about this horrible thing I had...” the need to go right into it. But they’re like, no, they might not have space for your story. So if you have space for someone’s story, make yourself available if you see those kinds of things. Like sleeping more than usual, eating more than usual, eating less than usual, etc.

Dr. Joy: I was going to also ask. I think traditionally there has been this information around like the means by which people die by suicide, it also feels like, has had a bit of a gendered piece. Historically, we've heard about women dying by suicide by maybe cutting or taking pills, whereas typically we see men do more violent (I think) kinds of things like using firearms or jumping. And it definitely feels like we are seeing some differences there. Is there anything that you can point to or information that will be helpful in understanding the methods that people choose to die by suicide?

Dr. Wade: Yeah. Again, it's kind of at that intersection of social class and gender. Historically, we call it internalizing and externalizing. What you would say is more violent, those are externalizing behaviors. And then internalizing behaviors are the things that women are more likely to do, like taking pills. But now, I would say as women are in these roles that are traditionally masculine, it's just not surprising that they're also taking on behaviors that are acceptable in these new spaces. Like the binge drinking. If you talk to women who might be depressed and they’re full time moms or they’re full time homemakers, they're probably not going to the bar and having six shots later. But then if you talk to professional women who have high demand jobs, they might be going to the bar for five shots afterward with everyone there.

I think as we enter these new spaces, we have to be cognizant about not changing who we are. Because it's easy to adapt to any space you enter, it is a socialization process, people teach you how to fit in wherever you go. But you have to remember, if this is starting to feel so stressful, that I have to engage in all these terrible behaviors just to cope, then there's a larger problem here. And that's when you start thinking about therapy, exercise, changing your diet, etc.

Dr. Joy: But you know, as you say that, Dr. Wade, it feels like it would be really hard to resist that. Because often, there's only one of us there. And so I think what is also protective for us as black women is having a cohort of us that we can kind of reality test with. Like, okay, is this weird? But if you're the only one, like if you are the only black woman on a faculty or you're the only black woman who's a chair of a department, it may be harder to know when you are adapting versus this is what I need to do to actually like maybe keep my job and continue to be successful.

Dr. Wade: Absolutely, and that is a major problem. Myself is not excluded, I've been the only black woman lots of places and found myself engaging in masculine behaviors or unhealthy behaviors. You're right, it is hard, but I think these conversations are important because every major social issue first had to start with conversations. I think, black women, there's going to be a lot of us (and black men) who are the outlier at work. It's just a fact. But then we can create a community among those outliers, like a space like you created, where other black people (they don't have to be in the same city) can come together and share space.

Yes, it is definitely hard to resist a socialization process, especially if you're new in your career because you don't want to look like “oh, I don't want to hang out with you guys.” You're like defying stereotypes with every decision you make. You don't want to like the angry black woman, you don't want to look like the standoffish black man, so you join the party. However, you do need something outside of work to keep you sane and to be a safe space for you to vent and stay on top of your self-care.

Dr. Joy: Dr. Vance, I want to go back to this term that you introduced. This idea of high functioning depression. I will admit that I have some very mixed feelings around this term. One, I'm not quite sure where it came from. It feels like all of a sudden, we were hearing more about like high functioning depression. And I think it is a bit of a misnomer because we know that depression can look lots of different ways. I'm not quite sure why there's the need to say that it is high functioning because we know that depression can look a lot of different ways, but it has risen to popularity. And definitely recently, we've seen more stories around people experiencing what they've called high functioning depression. Can you say a little bit more about that term and how it may be related to suicidal ideation?

Dr. Vance: Yes, yes. Dr. Joy, I agree with you. I've been thinking a lot about this term. Why would people use the word high functioning with anything? And I got to really thinking about that and I was like, well, if I'm thinking about it in terms of disparities, if I'm thinking about it in terms of black and brown communities, I first go to I'm going to say something is high functioning when it's a behavior that stigmatized. I have heard people use the language high functioning alcoholic. I'm a high functioning drug user. I have high functioning depression. I still believe this way for us to add an element of something that’s stigmatized to say “but I'm not them.” I'm not dealing with that. I have a control over it.

Because I agree. I think that we as individuals in our own different identities experience a lot of different things, and depression (as we're talking about right now) may show up very differently in me, it may show up very differently in you and very differently with Dr. Wade. And guess what, in seven days, it may then change again in terms of how we are dealing with those symptoms. And really to think about what a diagnosis of depression means. Everybody that’s sad is not dealing with an actual mental health diagnosis of depression. The high functioning language, to me, I think is a way to just make it look okay to everybody else and another way to mask. And for black women particularly, a survival skill that is killing them.

That high functioning and using that terminology, specifically for black women, is a mask, a survival skill, and a survival skill that I believe is what is leading to more black women dying. If we go back to what we were talking about in terms of being strong and not showing vulnerability and not showing emotion, and it's not okay for me to feel a certain way, then I want to keep up this image that people are creating for me, and then saying that I'm high functioning. Again, I think if we were to go back and even talk to people in other disciplines or maybe who study substance use and substance misuse like I talked about a few minutes ago, it doesn't make depression go away. It doesn't make substance use go away. If we talked about it in an eating disorder realm, it doesn't make the underlying issues and concerns and symptoms go away.

Dr. Wade: I just want to extend that a little bit, the idea of functioning really just being an adaptive strategy because it is and I want us to really, really start having conversations about our mental health and our behaviors. Because it seems like help or vulnerability are curse words. Instead of me being someone who needs help, I'm a functioning alcoholic, I'm just fine. But it's like, let's really sit in how ironic that is–to be a functioning alcoholic–and let's really talk about how you have this alcohol desire for a reason.

I'm just really excited about the future because I really think black women we’re done being strong and we want to redefine what that means. Strong means getting help, strong means saying I can't do it all, strong means saying not today. “I was invited but today it doesn't feel right, so I'm gonna stay home.” I'm excited about that. But in the meantime, I also want us to have these conversations because there are still so many of us that didn't grow up in this new era with self-care and check-ins. And so if we can continue to reach folks who weren't brought up like this, maybe we can change some minds and maybe we can help some folks get the help they need.

Dr. Joy: I would love to hear from you, we've touched on a number of some of the misconceptions, I think, as it relates to suicide in the black community. Are there other things that you want to talk about that you feel like commonly come up, that people kind of don't understand? Or maybe you want to add some nuance to as it relates to this conversation?

Dr. Vance: Yeah. I don't want to miss more of the macro level, larger level things. If we're talking about gender racism, specifically for black women. A lot of the work that I'm doing, specifically with my social work students as well as other mental health providers, is really helping people shift and understand that we need to work from a very much social justice framework, a human rights framework, and an anti-racist framework. I believe that from a prevention and intervention perspective, we have to continue to dismantle systems of oppression. There's not an in between. You're either going to be for human rights or you're not. You're either going to be anti-racist or you're gonna be racist.

We have to change that in our professions. Because if we've all been trained and educationally trained and practice-trained from that lens of white supremacy work and culture, that we're just looking at the individual. And it's not the individual’s fault, it's not the black woman's fault that she's being subjected to racism and sexism. It's society's way that they're dealing with everything that encompasses a black woman in this world and we've got to work on those levels. And I think that's where everybody has to get involved, it can't just be the mental health professionals. It has to be all of us really taking that shift. We don't have a choice anymore. Like it's gonna continue and I think the younger generation, like Dr. Wade said, they're not gonna be quiet anymore. Unfortunately, we're still losing people but they're not going to be quiet. And I think we have to tap into the generation that is going to continue to shake the rooms and help make some of these changes. We need more people that are standing in platforms like I'm standing in and calling out what it is, and it's whiteness and we have to change it.

Dr. Wade: One other thing to the young folk is we need you. We need black women in these fields–psychology, sociology, social work, community health, public health. You belong here. The way we talked about what the literature knows about black women's suicide, the answer being not much, that's ridiculous. In all facets of black womanhood, many things are understudied. Without you all coming along to join us, it will continue to be that way. The best way to figure out what the problem is, solve the problem, prevent the problem, is to have well intended, non-biased researchers, so we need you black women. You deserve it, you belong here, and people who are here are happy to mentor you.

Dr. Joy: More for my conversation with Dr. Wade and Dr. Vance after the break.

[BREAK]

Dr. Joy: I do not want to open up a can of worms or upset you, because I'm sure this conversation is multifaceted, but what is the funding looking like for people who want to do this work? I know there are huge grants, I think, that come out every year around suicide prevention. Are you finding that there is money being poured into the area of studying suicide and suicide risk for black women and girls?

Dr. Wade: To be honest, I thanked the protests for racial justice regularly. The NIH (the National Institute of Health) has sent out many calls for health disparity research. Before 2020, I couldn't get funding, my research was just like way in the margins. But now that America's eyes are opened, this is the moment. They have a lot of money for health disparities–at the person level, at the structural level, at the community level. They have money for universities to partner with clinics, community centers, you name it. I don't know how long this is gonna be, but I'm very grateful for this current moment of social justice and the awakening of America.

Dr. Vance: Specifically for suicide and suicide prevention, The Congressional Black Caucus published a report a couple of years ago ringing the alarm about the black suicide crisis. One of the calls to actions were for entities like the federal institutions (NIMH, NIH) to have more grants but also to fund more black researchers. And that is something, as like Dr. Wade was saying in terms of not being funded, I do think that that is a start. I can tell you that there's a lot of teams. There was recently a request for an application for a suicide grant with NIMH (National Institute of Minority Health). A team of us led by a black woman researcher looking to culturally modify and adapt care coordination intervention for black youth and children, and that is something that... we responded to that request.

And it's important that we did that also because, what Dr. Wade just said, it's actually going into the communities and working with the communities. Working with the pastors working with the families, and also working with black mental health providers and professionals with the families. The other thing Dr. Wade and I talked about last week was there's not enough black researchers and so we need well intentioned, we need non-problematic allies, and I am one of those people and I continue to show up in spaces and ask that people start seeing things differently. I'm joining with Dr. Wade, I'm joining with a lot of the women that I research with and the communities because it's not about us going in and thinking that we know everything. We can't be saving everybody. Again, that's the perspective, that's how we've been taught, that's how we've been socialized. It's really important that we work with communities and people who have the lived experience of what's going on in everyday lives.

Dr. Joy: Thank you for that. Dr. Wade, you at some point talked about how we can intervene to support peers and friends and colleagues who we think may be feeling suicidal. What other things can we do to support people who may be struggling in our lives? You see a lot of this conversation around check in on your friends, check in on your strong friends, and I don't know that people always know what that means. Can you share with us some tips and strategies for how we might be able to support people who may be suicidal in our lives?

Dr. Wade: You know, I just want to add. Before I was an academic, I was a community health worker so another message I do want to deliver is stay in your lane. Because sometimes people who are not trained therapists might overhelp and it's not helpful. A great help is actually referring people places. One of the wonderful things about the internet is you can find resources all over the place for suicide prevention hotlines, mental health services. You can go to websites and handpick a therapist who looks like you, who specializes in people like you.

I would say be a social worker, don't be a therapist. Help them get to the resources. Sometimes being the ear is good. If we're talking about suicide, if we're at that level of hopelessness, then I don't think the common relative is best suited to offer an ear. If we're talking early on and it's just a bad day and you want to help them avoid accumulating bad days, then yes, be that voice. Let's go for a walk together. That's one coping strategy that I used through the whole pandemic. Another colleague of mine, we would meet at the park three times a week and just walk for miles. Because it's so freeing, you can just get everything off your chest, breathe in some fresh air, get centered.

I don't want to tell everybody like there's a certain exercise that works because it has to be what works for you. But just engaging in something that's healthy, that can help you feel reinvigorated. You could do that with somebody, black women in particular love sisterhoods. The research I've done on diet and exercise, that's always the key takeaway–they want to do it with their group. So if somebody in your group needs you, then hey girls. Right now, one of my best friends and I, we get on Zoom at six in the morning, we're in two different states and we work out together. Do that. Make a sisterhood and promote health together. But again, also stay in your lane. If it got too far and it's time to talk to the pastor or the therapist, just be more of a bridge to help them get to the resources they need.

Dr. Vance: I think what Dr. Wade said is important. I think that one of the things that we hope to do and want to do more with communities is help them in being able to ask the questions and knowing when they do need to refer out. I know in Florida, we did a lot of trainings–question, persuade and refer. Also, we know that families or people that have concerns are gonna go to people that they trust. They are going to go to the pastor, they are going to do those things. And so one of the initiatives that we're working on is really training community health workers and faith-based organizations to also be able to provide them and, like I said, link with black providers and communities.

I think that it's important that we do find our village. I think that we need that support. I know that COVID has really harmed the way that most communities that live in collectivism–and love their family support and their neighborhoods and their villages–I think it has caused some issues there so I know that we haven't seen some of the things that are happening yet because of that. But I do think that it's important for us to also ensure that we're getting the community the resources that they need to be able to help their loved ones. They're not gonna come to us if we're not showing that we are able and also responsive to the needs of difference. And so I think we still have a lot of work to do, but I am eager and excited in that (unfortunately) due to a lot of the things that have happened, that there is some attention. But just like any other movement, we can't lose momentum, we can't lose focus. If anybody's been paying attention to the news, you might not hear about it when it happens but there's a lot more black people, a lot more black men and a lot more black women that are dying by suicide. We have to remember that they were not always men and women, they were boys and girls. And I think we have to start really thinking about things on different levels.

Dr. Joy: Yeah. And it may be too early to tell, but are you already seeing some of what the mental health impact will be on the other side of the pandemic and how that might relate to suicide numbers? Is there any information that's available yet?

Dr. Wade: Yeah. I've actually been doing another project about COVID risk. It’s really bad for black women in 2020, '21, '22. Like literally, when we look at essential workers, who were the essential workers? Who were the people on the frontlines who were cleaning buildings who were ringing people out at grocery stores? Who are the people that were drawing blood at the hospital? Predominantly black women. Then when we look at people working from home, who are the ones most likely to have to balance a job and child rearing from the home? Black women. Then we look at preexisting conditions. Who were the ones going into the pandemic with poor health, who were much more likely to contract COVID? Black women. Suffer from COVID? Black women. Die from COVID? Black women. It's like every way you can look at the COVID effect, it's going to have a worse impact on black women. While also sitting at home, looking at the Breonna Taylor story unfold, just everything that's going on. Who's gonna love the black woman? That’s just the final question.

I would say I want to be a hopeful person, but I think the impact that this pandemic is going to have on black women, it could be huge. The one good thing, though. I did pre and post pandemic focus groups with strong black women. During the pandemic, we reconvened our focus groups and asked them what is it like to be a strong black woman with all these things going on? And they were saying it was actually freeing because for once everybody was crying. You know, where we've had to live our whole life never crying–when everybody's crying, you're finally allowed to cry. So many black women talked about just letting it all out, engaging in self-care, not having the pressure to have their hair done, their eyelashes on. Just so many of the aspects of our gender that can be detrimental to your health. It was like all bets are off, I'm done with this. I'm a human and life sucks right now. If we can hold on to that, then that would be amazing moving forward. But the honest truth is the economic impact, the academic impact, the sociopsychological impact, I don't even know, it’s a 50-50. We might pull out as the superheroes or it really might show a dip in our mental health.

Dr. Joy: Which is the complicated piece, right? Like that's the whole part we've been talking about. If we pull out as superheroes, that means we have extended ourselves far beyond capacity yet again. But in essence, it feels like this is what it always comes back to; us trying to save ourselves and like scrapping and scraping to try to do it by any means necessary.

Dr. Vance: Yeah. That made me think also, Dr. Joy, about how we look at resilience and not like using that term. Like, oh, you've got this. You’ve got all the protective factors you need, black woman, so you're gonna be fine. Or this is what you have to do. I think we also have to shift resiliency to like transformation and thinking about those things. And I also agree with you, Dr. Wade, what you said. I know in 2020, we saw the death rates increase more than 30% for black girls and young black women. I think we were looking at the ages of like 10 to 24. To your point, I mean, if you think about the complexity of everything that has happened over the last couple of years, and where do you see the intersection of the black woman? The black woman is the mom of the black boys or they are the Breonna Taylors. You know, the black women, all of the things that you just said. And that intersection, again, of looking at that race and that gender.

And I really do feel that that's the community that's getting hit hard because of more of the structural inequities that continue to take over like a plague, honestly. I mean, that's really what we're dealing with when we talk about pandemic and endemic racism. You know, what can we do? But that is an age range, developmentally, that I would like for us to pay attention to. I'm hoping the work that we're going to do and the access that we have to the students that we work with at North Carolina A&T, the community members, that they know that there are people that are really looking at this and that we really do care and we want to stop it. It's preventable. We’ve just got to figure out the right things at the right time and stay true to it and not give up.

Dr. Joy: Dr. Vance, I will ask you this question. What words of encouragement would you share for people who feel personally responsible for someone dying by suicide? Parents, friends or loved ones who feel like they maybe missed some signs.

Dr. Vance: Grief is so hard, grief so hard. Most importantly, I think just like everything else that we were talking about, you do have to extend grace to yourself. More than likely, first of all, it's not your fault. You didn't miss anything in terms of something maybe specifically that would have let you exactly know that. But in terms of just really words of encouragement, you are not alone. There are other people that have also experienced loss at the level that you have and I would encourage you to find that space. Find that group of people that know what you're going through and can share those lived experiences. It's a journey and there's a lot that we don't know. Hopefully, the more that we do know, maybe you all can also get involved and help us understand things that we didn't even know. But extend yourself some grace, for sure.

Dr. Joy: You bring up such good points there, Dr. Vance, because I think it is very complicated. Because what we do know is that people who have been maybe chronically suicidal or who have had suicidal thoughts for some time, sometimes you will see an increase in their mood when they are like finally preparing to die. Which I think also confuses people because it's like, oh, I just talked to them the day before, they were in good spirits. And what we do know is that sometimes when people have made peace with their decision, there is a sense of peace there and so you may see a difference and a maybe more upbeat mood that would maybe confuse you and let you think that nothing's wrong.

Dr. Vance: Absolutely. And I think if we focus on, oh, when they did that we could have done this. Or, oh, I should have noticed that. I think it's a rabbit hole of so many things that’s just contributing to your guilt and some other things that may be happening. And you also should find support in helping you cope with the things that you're dealing with as a result of a loss by suicide that's often something that we don't understand. And to another point that a lot of people think there's some other connotations to it, like why would they do that to us? Why should we live without them? There's a lot of things around that that we still don't understand.

Dr. Joy: And then a question for you, Dr. Wade. What would your response be to people who believe that people who died by suicide are selfish?

Dr. Wade: That is a big question. I would say when we talked about the key factors that are associated with suicide risk and we talked about hopelessness, I just can't really wrap my mind around someone who's absolutely wholeheartedly feeling hopeless also being selfish. Those kind of seem like mutually exclusive places to be. I guess you would say they’re selfish because they left their family behind or their kids behind. But when you're at a point where you have nothing to offer your kids physically, spiritually, emotionally, I don't think selfish is an appropriate word to use there. And I think people get to hopeless after so many other incidences and so I think we need to think about how we treat our family members that are troubled. Because it's a process to get to isolation and hopelessness. I think, first, selfish is just the wrong word. And I think again we just need to go back to the early days before it got to hopeless and love on each other.

Dr. Joy: Thank you for that, Dr. Wade. Well, I am so thankful for you both sharing your expertise. Oh, my gosh, I feel like I could talk to you, because there's just so much! So much to unpack there but I know we don't have all day. Can you tell us, where can we stay connected with you so that we know about the new work that you're doing? Can you share your websites as well as any social media handles that you'd like to share? You can go first Dr. Wade.

Dr. Wade: The two outlets that are best to reach me would be LinkedIn or Instagram. On LinkedIn, just make sure there's nine letters in my first name. That's where everyone goes wrong. Jeannette Wade. And on Instagram @Dr.J.Wade.

Dr. Joy: Perfect. And what about you, Dr. Vance?

Dr. Vance: The best way to connect with me is on Facebook and Instagram, @DrMichelleVance. Hopefully, Dr. Wade and I will be able to also share with you any new things that we do. People can access us at the university. We are at North Carolina A&T State University. But I think that we're gonna be out doing a lot more things in the community and together, so we'll just make sure that we share our information. And thank you so much for this platform, for sure. I love everything that you're doing and I think that it's important that we're having these conversations as well as other conversations. I just want to thank you again for inviting us here.

Dr. Wade: Absolutely.

Dr. Joy: Thank you both. Thank you, I appreciate it. We will be sure to include all of that in the show notes for the show. I'm so glad Dr. Wade and Dr. Vance were able to share their expertise with us today. To learn more about them and their work, be sure to visit the show notes at TherapyForBlackGirls.com/session249. In the show notes, you'll also find links to resources that may be helpful to you if you're struggling with suicidal thoughts, supporting someone who is struggling, or if you've lost a loved one to suicide.

If you're looking for a therapist in your area, be sure to check out our therapist directory at TherapyForBlackGirls.com/directory.

If you want to continue digging into this topic or just be in community with other sisters, come on over and join us in the Sister Circle. It's our cozy corner of the internet designed just for black women. You can join us at Community.TherapyForBlackGirls.com. This episode was produced by Fredia Lucas and Elice Ellis, and editing was done by Dennison Bradford. Thank y’all so much for joining me again this week. I look forward to continuing this conversation with you all real soon. Take good care.