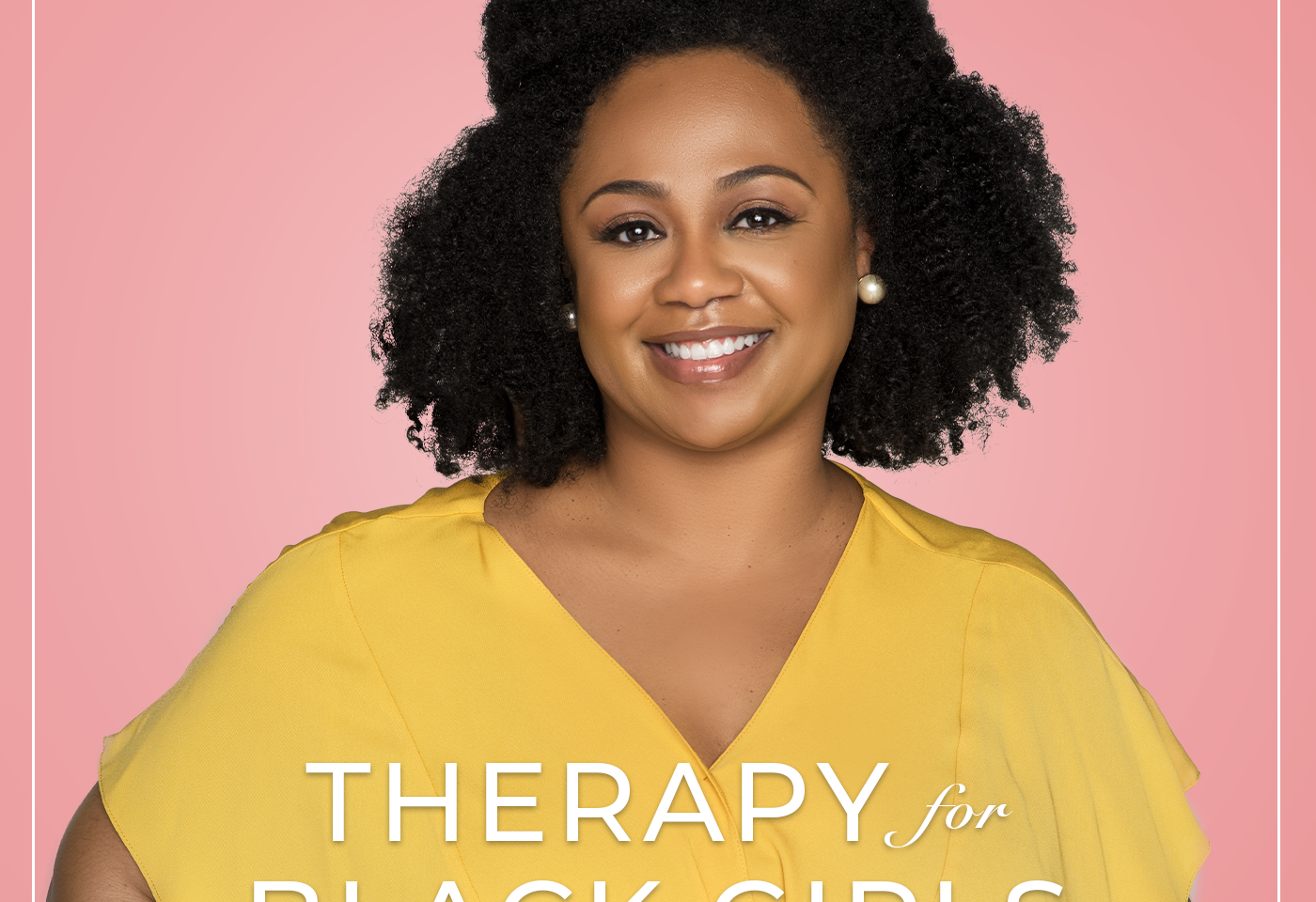

The Therapy for Black Girls Podcast is a weekly conversation with Dr. Joy Harden Bradford, a licensed Psychologist in Atlanta, Georgia, about all things mental health, personal development, and all the small decisions we can make to become the best possible versions of ourselves.

Watching reality tv shows are one of my favorite pastimes. It’s been really interesting to see how programming in this space has developed over time and to follow the commentary. And what has been most interesting is the way the space has been accommodating, or not so much, to Black women cast members and Black audiences. To help us explore this world, today I’m joined by Dr. Racquel Gates. Dr. Gates and I chatted about the complicated nature of Black women’s representation on reality tv, how audiences often respond to majority Black casts, the stereotypes that are both upheld and dispelled through reality tv, and the changes that often happen between season 1 and 2 of a show.

Resources

Visit our Amazon Store for all the books mentioned on the podcast!

Where to Find Dr. Gates

Twitter: @raquelgates

Stay Connected

Is there a topic you’d like covered on the podcast? Submit it at therapyforblackgirls.com/mailbox.

If you’re looking for a therapist in your area, check out the directory at https://www.therapyforblackgirls.com/directory.

Take the info from the podcast to the next level by joining us in the Therapy for Black Girls Sister Circle community.therapyforblackgirls.com

Grab your copy of our guided affirmation and other TBG Merch at therapyforblackgirls.com/shop.

The hashtag for the podcast is #TBGinSession.

Make sure to follow us on social media:

Twitter: @therapy4bgirls

Instagram: @therapyforblackgirls

Facebook: @therapyforblackgirls

Our Production Team

Executive Producers: Dennison Bradford & Maya Cole

Producer: Cindy Okereke

Assistant Producer: Ellice Ellis

Session 218: Exploring the Landscape of Black Women In Reality TV

Dr. Joy: Hey, y'all! Thanks so much for joining me for Session 218 of the Therapy for Black Girls podcast. We'll get into the episode right after a word from our sponsors.

[SPONSORS’ MESSAGES]

Dr. Joy: Watching reality TV shows is one of my favorite pastimes. Some of my favorites have been Trading Spaces, early seasons of The Real World, and of course, The Real Housewives. It's been really interesting to see how programming in this space has developed over time and to follow the commentary. And what has been most interesting is the way the space has been accommodating, or not so much, to black women cast members and black audiences. To help us explore this world, today I'm joined by Dr. Racquel Gates.

Dr. Gates is an associate Professor of Film at Columbia University and the author of Double Negative: The Black Image and Popular Culture. She received her PhD from Northwestern University’s department of Screen Cultures, and holds an MA in Humanities from the University of Chicago, as well as a BS in Foreign Service from Georgetown University. Currently, she's working on her second book titled Hollywood Style and the Invention of Blackness, for which she was awarded an Academy Film Scholar grant by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in 2020. Her writing appears in both academic and popular publications such as the New York Times, The Los Angeles Review of Books, and Film Quarterly. She lives in Brooklyn with her partner and two sons.

Dr. Gates and I chatted about the complicated nature of black women's representation on reality TV, how audiences often respond to majority black casts, the stereotypes that are both upheld and dispelled through reality TV, and the changes that often happen between seasons one and two of a show. If there's something that resonates with you while enjoying our conversation, please share it with us on social media using the hashtag #TBGinSession. Here's our conversation.

Dr. Joy: Thank you so much for joining us today, Dr. Gates.

Dr. Gates: Thank you so much for having me.

Dr. Joy: I am so happy to have you here. Reality TV is like one of my favorite things to enjoy so I love to talk to people who are researching in this area. Can you start by telling us a little bit about what fascinates you about media studies and how you got into studying reality TV?

Dr. Gates: Sure. What fascinates me about studying media but also film is that I think that film and television are these sources of connection between people. And I think that sometimes in spite of our backgrounds, sort of our shared experiences with different movies or different television shows allow us to tap into something and sort of form a site of human connection. I also think that sometimes we can work out our own feelings and experiences vicariously through watching film and television. And I think that's where reality television is particularly unique, because it's so much about sort of daily lived experience. And of course, that's like played for drama and for comedy and all kinds of things but I think that at its core (reality television in particular) the draw is this sort of very real connection with the cast members. And I think that's a huge source of pleasure for the audience.

For me, how did I get into studying reality television? By training, I'm a Film and Media Studies scholar and I'm also a fan of reality television. And there's a point where, at least for me, when I was sort of reading like newspaper articles or just sort of listening to the ways that people were talking about reality television, it always seemed to sell the genre kind of short. And it seemed to presume a lack of sophistication on the part of the audiences which are primarily women.

And for me, a light bulb went off because that's typically what happens when you are talking about genres that are primarily enjoyed by audiences who are not like straight white men. And so for me, I really wanted to sort of turn a segment of my research to reality television to really sort of get at the nuances of what makes it so pleasurable but also (I would argue) so powerful and so enduring.

Dr. Joy: It feels like the genre really has kind of expanded. Like I think... I'm guessing, you probably know this better than I do. Like is The Real World kind of like our first real foray into reality TV? Can you talk just about like how the genre has expanded beyond stuff like Real World?

Dr. Gates: Sure. I mean, people always cite The Real World, like that 1991/1992 moment. I mean, I think of that as like the dawn of the contemporary era of reality television. But if we're thinking about the nuts and bolts of what makes something reality television, like the idea that it's unscripted, the idea that we're getting like a behind the scenes look at either a person or a community that we don't normally get, then I'd argue you have to actually go back to the 1950s. And something like Edward Murrow’s Person to Person, which was a television show where the journalist would go visit the home of celebrities and get this sort of candid interview where they would talk about various things in terms of their personal life and their professional lives.

You have to think about something like Candid Camera, that television show which is about playing jokes on unsuspecting people. You could also think about all of the game shows that became really popular in the 1950s. There's a television show that I like to teach in my reality TV class called Queen for a Day which was this show where women would come on and they would sort of talk about all of the things that were going wrong in their lives. And if like the audience thought their sob stories were pathetic enough, they would win something, they'd win a prize. And it's clearly a predecessor to something like Extreme Home Makeover, which is a show that we're more familiar with now.

And also throughout the film sociological experiments that happens like in the 60s in the 70s, the Stanford Prison Experiment, things like that. And one of my favorite examples that I like to teach, JFK’s filmed televised birthday party at Madison Square Garden, where Marilyn Monroe comes out and sings this very sort of sexy version of Happy Birthday to him as his wife’s sits in the front row and watches it. So like when you think about what makes reality TV reality TV, I think that (especially American) audiences have been engaging with that type of thing well before we had an official name for the genre.

Dr. Joy: Yeah, and as you were talking, it also made me think of this show with Regis... Was his name Regis? Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous.

Dr. Gates: Oh, with Robin Leach, right?

Dr. Joy: Yes.

Dr. Gates: Yeah, Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous, which is totally the predecessor to Cribs. Yeah, absolutely, absolutely.

Dr. Joy: Cribs, yes, that’s fascinating. Yeah so now you’ve mentioned a couple of things. We still have The Real World type kind of shows where we have things like Extreme Makeover, we have the game shows; are there other types of programming that kind of are also considered reality TV?

Dr. Gates: I think anytime you're thinking of unscripted, I think something like An American Family, which was a docuseries that aired in the 70s which was about sort of looking at... It was like a domestic drama, sort of seeing what was going on with the family, and the parents eventually split up, and one of the sons is gay and he leaves their town and he goes to New York. A lot of scholars sort of cite that as like the pre-reality TV text but I think that when you start like pulling the threads of all of the things that make reality TV reality TV, then I think we realize that a lot of shows actually sort of have fit into that for quite some time.

Dr. Joy: Mm hmm. You mentioned earlier that you feel like something that's incredibly powerful about the genre of reality TV is like the relationships (or parasocial relationships, I guess, in some ways) that people form with the cast members. Can you say more about like why that is so powerful?

Dr. Gates: What I think happens with reality television is I actually think it provides an opportunity for resonance and it provides an opportunity for empathy, and that's different for me than identification. Identification is that character reminds me of myself because their profession is similar or they look like me, you know, something like that. But resonance is there's something about what they're dealing with that connects with me. I don't have to have anything else in common with them.

I think about the Kardashians where even people who can't stand that show, whenever the sisters fight, I always notice this online that people will say, “I don't even like the Kardashians, but man, when she hit her sister with the purse, like, yeah, I felt that. I know that.” And so I think that reality TV, because of the unscripted nature of it, you get a lot of those moments, these sort of small things that connect with us on an experiential level that in any other context wouldn't really make for good television. Like it has nothing to do with the plot, they're not really good narrative beats. You get those moments and you get that in reality television because of the nature of what reality television does.

Dr. Joy: I want to just drill down a little bit specifically when we think about black women in reality TV. And so Heather B was of course on The Real World. But you were talking about like even before that, are there other instances where we can kind of trace the history of black women in reality TV?

Dr. Gates: Well, I think in terms of sort of before that, we had like black women celebrities who were on game shows. I mean we definitely get that. I'm thinking of like Lena Horne and Dorothy Dandridge being on these game shows, especially the ones that are focused on celebrity, and those are always sort of fun moments because you get to see them being silly and being... You know, I don't want to say being real because they're obviously still performing, but you get to see a version of them that's really different than their sort of very carefully curated Hollywood film version.

I actually think that if you go back to like the origins of cinema, like in the 1890s, you have these interesting moments where blackness is sort of both the side of performance and the side of authenticity. And so what I mean by that is early cinema, it wasn't like narrative yet. I mean, some things were sort of staged in little scenarios and some things were like “look at this black woman washing her baby.” Because so much of it was about just the fascination with the medium itself, not necessarily with the content.

And so I think in early cinema, you have this interesting slippage which is relevant to black women in reality today, where this line between are they being real, are they being themselves versus are they performing? Are they performing for the camera? That's not always clear and that's a little blurry. And I would argue that's part of the pleasure in early cinema and I think that's also part of the pleasure in contemporary reality TV. But that's also the kind of conundrum that leads to some of the debates that we have about representation of black women on reality TV.

Dr. Joy: Yeah, and so can you say more about that? I mean because, you know, we exist... Especially in the US, we know that there are stereotypes that people play into when they're casting particularly black women for certain kinds of shows. And so can you talk more about like how some of those stereotypes do play out? And the investment that the genre has in like casting certain kinds of black women.

Dr. Gates: I think a lot about Omarosa from The Apprentice when this topic comes up. You know, Omarosa who is like an almost cartoonish, like angry black woman, kind of like... I'll put this in quotes even though no one can see me, like “black bitch” type of character. Like a very, like typical TV villain. And I always remember seeing her on an episode of Dr. Phil after her season had aired, where she was talking about the backlash that she got and all this stuff. And he was like, “Well, you did that. You have to take responsibility for yourself.” And she said, which I thought was so brilliant, “There were a lot of black women at that casting. They could have picked anybody they wanted to. What I presented on the show was exactly what I brought to the casting. So is it me who’s sort of playing up a role that I knew would like get me on the show and get me airtime? Absolutely. But the producers didn't have to cast me they didn't have to give me airtime.”

She pointed out that on the season following her, there was another black apprentice cast member who barely got any screen time and they edited out all of her stuff. I think it gets really complicated. You mentioned Heather B and one of the things Heather B said pretty famously, when... I can't remember who it was. I think it was Tami Roman but it's sort of a later black woman on reality TV who was like, “the editing, the editing.” And Heather said, “Well, they can't use what you don't give them.” And that's true but also you can edit people in all kinds of ways, right? I think that audiences now, we're very savvy about that type of thing. But I think what we haven't necessarily talked enough about is that it's also about legibility. It's also about sort of the perceptions and the biases on behalf of the audience that they don't even realize they're bringing into their interpretation of the shows.

And so an example I think of a lot is when The Real Housewives of Atlanta premiered and that's the first black cast housewives show. At the time. Now there's Potomac, obviously, which was premiered, which was amazing. But anyway, when Atlanta premieres, I remember reading like housewives’ message boards. And I saw the women being talked about in a way I had never seen with any of the white cast before. So they were referring to them as lazy. You know, they kept saying things like, ah, they're just so big. Like things like that, right? I mean like things that were clearly sort of like stereotypes and tropes about black women that had nothing to do with the show, that had nothing to do with this particular cast.

But even saying things like “they're lazy and they're gold diggers” on a show that is literally about housewives, on a show in which when women had gone out and worked, I've also seen audiences criticize that as well. There's a constant refrain from The Housewives fans where people will be like, there's no real housewives on here. And then you get Atlanta where you have like housewives and they're called gold diggers and that has everything to do with perceptions of black women, regardless of what they do or don't do.

So you know, I think these things get tricky. I think editing plays a part, I think (obviously) cast members have agency in terms of what they choose to put on the show and how they choose to behave on the show. But I also think that audiences bring their own readings and their own lenses and their own perspectives when they're watching.

Dr. Joy: Yeah, absolutely. And if I remember correctly, The Real Housewives of Atlanta of course was not the first one, but like you mentioned, it was the first like kind of black cast.

Dr. Gates: Yeah.

Dr. Joy: But I feel like it was also the highest rated, wasn’t it?

Dr. Gates: Oh, definitely. I mean, Atlanta has... I don’t want to get my numbers wrong but Atlanta has pretty much (since it premiered) been the highest rated of The Housewives shows. Everybody knows that, everybody acknowledges that. And yeah, they were, I want to say they were third. It was OC, New York and then I believe Atlanta–I always get Atlanta and New Jersey sort of inverted in my head. But, yeah, just kind of out the gates, they were killing it in the ratings, you know? Yeah, absolutely.

Dr. Joy: Yeah. And you mentioned earlier like that a part of what is attractive about the genre is that people are able to kind of relate to the stories people share. But I wonder if there is something about like both the Housewives of Atlanta and Potomac, that non-black audiences feel like they cannot relate to the stories being shared by these women.

Dr. Gates: I mean, it's possible. There's an interesting thing that I noticed among who I'm presuming are white Housewives fans. I mean, I don't know, this is just me going off of message boards and Facebook groups and Twitter. Where people feel very comfortable saying, I watch all the Housewives shows but not Atlanta or Potomac. And they don't seem to feel any kind of way about saying that, you know what I mean? Which is interesting, right?

I think that one of the strengths, though, of the Housewives shows is that there's different ways in. And what I mean is that the Housewives shows on Bravo, like Bravo has a very different approach (in my opinion) than a lot of the VH1 reality shows, like Love and Hip Hop. And what I mean by that is Bravo, they call it the Bravo wink, and really what it means is that when you're an audience member, you're always kind of on the side of the producers against the cast. Like there's an invitation through editing and through all kinds of things for you to kind of snark on the women or for you to sort of like laugh at them if you so choose.

And so I actually think that Atlanta and Potomac wouldn't be on the air this long if white women weren't watching those shows. White women and white men, like that's just a fact. Like they wouldn't be on this long if that were the case. So I think that there are different ways in, some people watch it and identify with the cast and route for various cast members, some people sort of watch it to snark on the cast. I mean, I think that what we see especially with Atlanta (and I think that the sort of popularity of NeNe Leakes during the show and post-show) is sort of evidence of the fact that it's sort of like, as culturally specific of a cast member as she is, she has wide-ranging appeal and lots of people connect with her for all kinds of different reasons.

Dr. Joy: Mm hmm, yeah. And when you think about, like you said, like Potomac just premiered, like the new season. And so I feel like there is a distinct difference between like the first season of Potomac and the second season. Can you say more about those differences?

Dr. Gates: Yeah, I just think Potomac is the best of this... I just think it's the best of the franchise at this point. Like I don't even feel like that's debatable but that's...

Dr. Joy: Really?

Dr. Gates: Yeah.

Dr. Joy: Okay, I’ve got to hear you say more about why.

Dr. Gates: Okay, here's what I think is great about Potomac. First of all, Potomac is super culturally specific. I mean, you can have a black cast show that is not culturally specific to black people. So for me, I love Potomac because it's rooted in a place, like it's rooted in like the DMV area, like in DC, Maryland, Virginia, right? Those women have history there, they weren't all flown in, you know what I mean? I think about Atlanta, when Kenya Moore sort of joins the cast and she's great on the show but it's also really clear that she was cast and she moves to Atlanta to film the show. And that's different than somebody who grew up somewhere or somebody who's lived there and made a home there.

I also think that Potomac has that great thing where the cast, some members of the cast, they've known each other since before the show. That they gel, they have history. I'm so fascinated by like Karen and Gizelle’s relationship because, you know, when they fight that feels real. That doesn't feel like just some on the show stuff; that feels like years of whatever kinds of experiences that have led to whatever tensions they had. And that always feels more organic to me than what I think happens with some of the other shows when the cast are kind of like cobbled together and they don't have history.

I think, knowing that Potomac... I believe that the producers who work on Potomac (because each of the Housewives shows, they have different production teams, it's not like one universal team) knowing that their producers are black, I think that there's a different handling of certain material than you see sometimes on like other shows. I just think Potomac is so great and I think each of the women, they’re such strong cast members on their own, they have such interesting dynamics between them. Yeah, I just think it's fascinating.

But you asked about like the first season to the second season. That was your original question before I went off on that tangent. I think what you see with Potomac, it's sort of like it's analogous to what happens with all of these shows. Like the first season, I think everyone–the cast and the producers–everyone's trying to figure out what the show's going to be. There's like a lot of exposition, there's an emphasis on whatever the pitch was, whatever the theme is. You see that in something... this is not black woman, obviously, but like Jersey Shore.

Like a Jersey Shore is pitched as it’s going to be this show about Italian Americans at the shore. That first season, it’s like that’s all they're talking about but that's also likely all the producers are asking them about. Is how do you feel about what does being a “Guido” mean to you? Because that's like the focus. It's the second season, where everyone's kind of settled in a little bit but also I think when the first season is aired and they've seen themselves on television, that now you have this slightly different engagement.

This is a horrible analogy but I was thinking like Terminator 2 and there's this moment where they talk about when the machines became self-aware, like that's what kind of happens in the second season of a reality show. Is they’re like, oh, I need to go get a better weave. Like, oh, I need to get a better wardrobe, I need a glam team. But also, I need to think very carefully about what I'm doing on camera, what I'm presenting on camera, and how that's gonna play. And I also think that by the second season, the audience, we have our understandings now of who we think the star of the show is and how we understand personalities and certain dynamics. I mean, I always like the first season of the show, but to me the second season is like really where things start to get cooking.

Dr. Joy: Yeah, like when you really, really kind of get to meet the cast, like some of the real stories. Yeah. More from my conversation with Dr. Gates after the break.

[BREAK]

Dr. Joy: Another popular kind of type of reality show are like these dating, love kinds of shows. It does feel like there is like a particular kind of black woman that typically is cast for these shows. I’d just love to hear your thoughts about like are you seeing the same kind of thing or are there varieties in terms of like people who are cast?

Dr. Gates: Well, which shows in particular are you thinking about when you're talking about the dating shows? Like The Bachelor...?

Dr. Joy: Like Too Hot to Handle, Love is Blind. Well, The Bachelor, that's a whole kind of thing. Like that kind of show.

Dr. Gates: Dating shows are not like “not the thing” that like light me on fire in terms of a reality TV fan. But what I think is interesting about the dating shows is we tend to talk a lot about reality TV in terms of like the content, what's in front of the camera, instead of thinking about networks and thinking about audiences and things like that. What's interesting to me about like The Bachelor and whatever has been happening for the past couple of years with discussions about blackness and The Bachelor, is there isn't as much of a discussion about who's the audience for The Bachelor.

Like there's all of this kind of we got a black bachelor but the woman he loves like did some weird racist patch or whatever that story was. But to me, it felt really clear that you can cast a black person but if for instance your casting questionnaires is never change, if your approach to casting is the same, this wouldn't have been... I mean, I don't want to say it wouldn’t have been an issue, it wouldn't have mattered. But had the bachelor been white (and I'm assuming that for the one black bachelor they picked, the other four possible bachelors were white dudes) this wouldn't have been... this wouldn’t have made it to air, this wouldn’t have been an issue.

And so I think that when you're talking about, for instance, like slotting black women into that formula, like the formula is the formula. And so you're going to get a specific type of black woman because they're not necessarily like, they're not interested in... Diversity is a tricky word anyway, as we've watched the past year. But I mean not interested necessarily in like a diversity of black women. They're interested in like a phenotypically black body to slot into whatever they wanted for that show.

And I think dating shows tend to be much more formulaic than... I think dating shows, I think any kind of competitive reality show is really what I would say. Like competitive reality dating shows, but also like Survivor, The Amazing Race, versus candid reality shows? Like Real Housewives, Love and Hip Hop. I think the competitive reality shows tend to be much more formulaic and they tend to cast for type much more often and so I don't think it's ever really surprising that you see the same types recurring over and over and over again.

Dr. Joy: Yeah, and I want to kind of stick with your point around like really thinking about the different networks and like who their audiences are. You mentioned this idea of the Bravo wink, like that we’re kind of positioned to side with the producer. And you mentioned that you feel like that's very different from like what we would see on a Love and Hip Hop. But I'm also aware that it feels like the OWN Network has developed a different kind of like slate of reality TV. I'd love to hear your thoughts, maybe just about the differences between like what we see on which networks.

Dr. Gates: Yeah, I'm trying to... Which OWN shows in particular are you thinking of?

Dr. Joy: There's Put a Ring on It. Ready to Love, which I think is an interesting dating show. To me, the people who are on that show are very different than what you would see on a Too Hot to Handle. Also, what are the other ones? Love & Marriage: Huntsville, that’s kind of in the vein of like a Real Housewives, Love and Hip Hop, but not quite the same. So, yeah, that’s their slate.

Dr. Gates: There’s a couple things, I think that different networks just have different approaches to things. And so like I always compare Bravo and VH1 and I compare those two very often because they both have this kind of like late night soap opera like thing that they do. For instance, Bravo does that with its shows and VH1 does that with its shows, too. And to me, those are easy comparisons because you can see the tonal differences because so much other stuff is sort of similar.

What I mean by that is so you have the Bravo wink, you have a thing where there's a clip from Potomac where Wendy she’s just had like breast augmentation surgery. And so she's going to the doctor for a checkup and she's talking about this, she had her breasts done. But they cut to like a producer saying, “Have you had any other work done?” And she's like, “If I did, I’d tell you.” They cut back to the scene and then the camera scans down to her stomach and the clear implication is that she's had a tummy tuck. And like that's production kind of winking at us the audience saying, “You know she's not telling the truth, right?” Like, that's what that is. This is all unbeknownst to her. She has no clue that this is the kind of communication that’s happening between sort of like production and audience.

VH1 by contrast, to me, the tone of the VH1 is earnestness. So I think a lot about, I think it's the first season of Love and Hip Hop Atlanta where we got introduced to like Stevie J and Mimi and Joseline Hernandez. And Joseline Hernandez takes a pregnancy test like in a bathroom stall and the camera crew comes with her. And people have talked about like, oh, that's ridiculous that she did that on camera. But what I'm always fascinated in is the camera work in that scene.

The camera is focused on her face and it's just this beautiful close up where she looks beautiful but she also looks fragile and she looks like anguished and sad. And it's so close that you can see the tears coming down, it's this moment that the camera is making us the audience, making us the viewer, identify with her and connect with her. And for me, that's always been this powerful moment because when in pop culture are we ever asked to feel sympathy for the side chick? When are we ever asked to sort of identify with the woman who's like sleeping with this guy who clearly has a long-term girlfriend and partner? And so that feels really powerful to me.

I think that like if we're thinking about the shows on OWN, that's a different demographic as well. I mean, I'd have to sort of check the numbers but I'd be curious about the age demographic, I'd be curious about who they envision their audience to be and therefore what are the issues? I think the fact that it's focused on marriage instead of relationship suggests a slightly older audience than what the assumption is from VH1–which has to capture people from like 18 to 40. Whereas I think that OWN skew... Don't quote me on this.

Dr. Joy: I’m pretty sure they skew a little.

Dr. Gates: This is my guess, but like they skew a little bit older. But I think that that tone of earnestness is still very much a part of how OWN does this. In part, that's also the reputation of the network. And so for me it's really interesting to think about how things like that shape the show, shape how we view the shows even as viewers. Like what are we expecting to see if we know something's on VH1 versus OWN versus Lifetime versus MTV? Like we come to it perhaps with different sort of reading strategies.

Dr. Joy: One of the major critiques of reality TV, I think specifically as we think about like black cast members, is this idea of representation. About like, oh, what do white people think when they see black women fighting on TV? And so there’s still like this centering of the white gaze. And I think the argument can be made that I think a lot of like black projects have this burden, it feels like. Like they’re going to speak for the entire race. Can you talk a little bit about that critique?

Dr. Gates: Yeah, I think that what we see with reality television is this intensified discourse that's really been happening since the dawn of cinema. Like whenever we have talked about the black image in popular culture, period, the burden of representation is always the discourse. Like the politics of representation is always the thing that we're talking about. And to me, I think when you're talking about pop culture, I think it's the wrong question because I think what it does is it narrows down the possibilities. It takes a few things for granted that I would actually push back against. One is that people enjoy things because they identify with it. The second sort of assumption is that television and pop culture is like a role model type of thing, where like you see it and you want to imitate it, which has never been proven true anywhere.

These are always like the underlying assumptions. And so if you start with those as presumed facts, that leads you down a really narrow path which is like, is this good or bad for black people? And there's, I think, like kind of a DuBoisan double consciousness, which is how does this make us look? And the implicit thing is like, well, to whom? I think when you're able to sort of cast that aside of it as a consideration... I’m not saying that that's irrelevant. That as a dominant way of analyzing media, I think is faulty because I think there's so many other things to attend to besides like the politics of representation (which most media studies scholars challenge anyway.)

Like we don't think that media works that way and we certainly don't subscribe to what some people call a media effects argument, which is that like media makes people do things. The example that I've used a bunch of times is scenes where people fight. There's a scene from Basketball Wives where Evelyn Lozada gets so angry with someone that she like jumps up, runs across a dining table to attack this woman and like jumps off the table and goes at... It's insane. And I remember when that aired and people said, “Well, if little girls see this, they'll think that's okay.” And that's kind of like a logical leap; is it really grounded exactly in anything?

And what I would say is, well, why do we read it that way as opposed to fantasy, as opposed to emotional catharsis. Maybe you don't watch that and you're gonna like go out and like run across the table, but maybe you identify really strongly with that feeling when you're sitting at dinner and someone's jabbing at you and they're making little comments and like you're trying to hold it together but you feel like you could explode. Which I think is that feeling like a lot of black women have had in their workplaces in different stressful circumstances.

You know, there's something pleasurable about seeing somebody who has no bearing on your life being able to do that thing that you kind of secretly wish that maybe you could do. So that's how I read a lot of that stuff. I also think that the criticism of reality TV tends to focus on the most salacious moments and never on the quieter moments, which are the things that I actually think connect with fans more often. So, yeah.

Dr. Joy: More from Dr. Gates after the break.

[BREAK]

Dr. Joy: I'm really glad you shared that, Dr. Gates, because I hear that argument all the time. But of course I'm not a media scholar so I thought there was some truth to this idea of media effects. Like that people imitate kind of what they see. So where did that come from?

Dr. Gates: I think there's a couple of things. I'm sure that there’s sort of a different strain of media studies scholars who are more based in like psychology and the sort of comms studies who might make that argument. And I don't think that that argument is inaccurate but I don't think it's accurate for this particular type of media. Like do I believe that you can see so much violent content that you become desensitized to seeing violence? Sure, like that's media effects argument. Do I think that if you sit and watch Evelyn Lozada run across the table, that suddenly you're gonna lose all your good sense the next time you have an argument with somebody and run across a table? No, of course not, that's just silly.

So I think that what happens is that gets applied across the board and I also think underneath it is a lack of credit being given to the presumably like black audiences who are watching these shows. And I think you see that across all types of sort of art stuff. There's always this idea of like even with literature–well, you can't let these people have access to this thing. I mean, this happens, I'm thinking of the scholar Cathy Davidson's work about sort of the tension and the anxiety around the development of the printing press. Because there was this idea that like you can't just have literature and news be widely accessible. What do you do with these uneducated masses? You can't just let them have access to information. It's that same idea that some people cannot handle access to content.

Also, when we're talking about black people, I think that we (understandably, because of the history of film, because of the history of television and the ways that those are connected to racism and racist imagery) have a healthy suspicion of what these images do. Like we know that D. W. Griffith’s film, The Birth of a Nation, was used as a recruitment tool for the Klan. We know that but there's a distinction between using a film as a recruitment tool and thinking that showing people that film is the thing that made them racist. And that's not the same thing. I think we have to be really careful when we talk about how people engage with media because our real life experience is nothing like what those critiques say.

And I've heard this before where someone has said, well, you're a professor, you understand. I'm like you can't point to anybody that you know or have experienced who has like imitated a thing they've seen on reality TV. There's not some young promising girl on the Southside of Chicago where I'm from, who was like about to go off to college on a scholarship but then she watched Basketball Wives.

It's treated like it's reefer madness, you know what I mean? Like this sort of paranoia around these things that are going to ruin black people. I think that there's very valid concerns about black representation, particularly brown and black women's representation, but I also think that's one lens and there's multiple lenses with which we can be viewing these shows and talking about these shows.

Dr. Joy: In addition to Potomac, what are some of the other shows that you are really loving? And is there anything that you're excited to see like somebody who has done something really different with reality TV that you enjoy?

Dr. Gates: I mean, I gotta be honest. Like this past year, all of my viewing has just been shot because I have five-year-old twin boys, they were home from school for like a really, really long time. There was not a whole lot of viewing that was happening except for like Disney films. But I love Potomac, like I love Potomac. I love all The Real Housewives shows although this year has been a weird time. And I think partly because of like COVID production things that have made filming kind of bizarre, but also because they all are kind of trying to deal with racism in these very coarse inelegant ways, which doesn't always make for the viewing.

I was a huge, huge fan of Mob Wives when it was on in like 2010/2011. I thought it was one of like the first two seasons of that show, I will always say is some of the best television I've ever seen, scripted or unscripted. I just thought it was an amazing show. I was really into Jersey Shore for a very, very long time and still keep up with Jersey Shore. What am I excited about on the horizon? I'm kind of excited–this is like a broad comment–I feel like we're at this moment where reality TV has gotten very meta.

You know, it's not just The Real Housewives shows. Now we have The All-Stars Real Housewives Show which is going to air sometime soon, like we have. We have shows that are like very self-referential, where we're talking about the show as a show and we've seen that on a bunch of things–white shows and black shows–where they talk about production as part of the show. I mean, Atlanta was like that, the season with the bachelorette party and Porsha who slept with a stripper and who did it. So much of the storyline was about, hey, we thought we weren't filming and we have an understanding for what it means when we're not filming and Kenya, you broke...I mean, that's fascinating to me.

I wish I had specific shows I said I was excited about, but like that as a thing, that as a theme is fascinating because my question is, well, then where do we go from that point? If we're at the point where the shows are now about themselves, the show is very much about filming the show. Like Kardashians is that, right? This is their last season, the whole season is like, we didn't know how to tell the producers and we had them on and let's watch the old footage. I mean, it feels to me like we are at this moment where something is going to radically shift. Because like, where do you go from here?

And so I've said in sort of other places that I would rather refer to reality TV as a mode rather than a genre. Like it's a way of engaging. Because there's such a diversity within reality TV, the genre seems like to sell it short, I think. I'm curious to see like where this is headed now when we're at the point where a magazine like Us Weekly, it’s mainly reality show stars in there. Those are the celebrities. And the blurring of the line between who is like a “legitimate celebrity” versus who is a reality celebrity feels... Like what do you do with Bethenny Frankel? What do Nene Leakes? Like my dad knew who these folks are. People who never watch the shows know who they are.

I think we're at this really kind of fascinating moment in terms of sort of seeing the collapse of high culture and low culture and different forms of celebrity. We just came off a presidency of a reality TV cast member, when we had the kind of big slate of Democratic candidates and Bernie Sanders had Cardi B doing videos with it. It was like this moment where I thought, are we still gonna pretend like reality TV doesn't matter? Because we got one reality TV dude in the White House and we had Cardi B from Love and Hip Hop like essentially campaigning for Bernie Sanders. Like something has changed, something has shifted. So I don't know, I'm just curious to see what happens at this point because I have like no predictions, honestly.

Dr. Joy: Right, right. And it seems like with the rise in social media, like people on TikTok are amassing some of the same numbers as a show on a VH1. You know, so to me it’s interesting that it almost seems like the new wave of reality TV, so to speak, might be existing like in a place like TikTok.

Dr. Gates: I think we also are in this moment where even our understandings of what constitutes media has changed. Like when we say TV like what are we talking...? I mean, especially thinking about what's happened during COVID. There's two strains we could think about. One is the fact that social media has become so prominent that most of the beefs that are happening on these reality TV shows like originated on social media somewhere and the shows have to do it, they have to show screenshots of like Twitter and people's DMs. And those are things that people are leaking and then the producers are like, crap, we’ve got to pull that into the show now, right?

But I think they also expect that we, as viewers, were totally on Porsha's Instagram and we totally saw that. Like they know that we know and they're reacting to stuff now. They can't just control, they can't just throw out the story and expect us to buy it. We're like, no, no, no, because I saw that they unfollowed each other and I know that happened two weeks ago.

But I think, as you point out, the other thing to tap and particularly within COVID, when you have production in film and television grinding to a halt or being severely compromised because of the pandemic, when you have the rise of TikTok, when you have the rise of social media influencers. And now we have this kind of additional breakdown, this additional blurring, what is TV anymore? Is it like me sitting in front of like my actual television that's like wall mounted? Or is it me with my smartphone.

Like which one of those is the medium? Which one is sort of the dissemination of content? When you have, I can't think of her name but a famous TikToker who then is on Keeping Up With The Kardashians as a friend of Kourtney. And I have no idea who she is so I have to go to Tik and find out. I think that what we're seeing is not just shifts that are happening in terms of the content that's on the shows, but even like the mediums. Like is TV still going to be the thing? Are we still going to be tuning into E or Bravo or whatever? Or are we going to be sort of primarily on one of these social media or streaming platforms? As a media study scholar, it's a weird time. It's exciting but it’s weird.

Dr. Joy: Yes, right. Okay, so one last question before we wrap up because I feel like we could talk about this forever. As you were talking earlier about like the messages that surrounded The Real Housewives of Atlanta cast. And I don't know enough about like the positioning of what Married to Medicine was, but it almost feels like that was like an answer to like “oh, these women aren't doing anything.” And so then we cast these Real Housewives type (I feel like) women, but some of them are actually physicians. Do you know anything about the positioning? Like, do you think that that was a response?

Dr. Gates: Look, I don't work at Bravo so I can’t say. I can't say definitively but if I had to guess, when Real Housewives of Atlanta comes out and it comes out in 2005/2006. And it comes out... Basketball Wives, which is not on Bravo, which is on VH1, Love and Hip Hop, they all get lumped together. And you notice that when you start reading like newspaper critiques and stuff like that, they just lump all of them together, which is its own form of like kind of racist gendered like stereotyping because Real Housewives of Atlanta is a very different show than Basketball Wives.

But I think that what happens is there's so much critique and there's so much kind of uproar about that that, yeah, I absolutely think that Married to Medicine is supposed to be like the corrective. Okay, we're going to show professional black women and women married to doctors, etc., etc. It's interesting because a lot of times I've also noticed like people use the same stereotype around those women. Which at some point like, yeah, maybe it's the casting, maybe it's the production or maybe it's the audiences. Maybe there's this way where like audiences are not ready to see black women in all of their complexity, which means that you can be professional and also be kind of messy sometimes. And like that's being human.

But I think that in the realm of media, where black people and black women have so often been portrayed as being inhuman or subhuman, human doesn't feel like corrective enough. We want like Clair Huxtable, we want sort of the perfection of Olivia Pope who never has her hair out of place. And I think that it's an unfair standard but I also think we close ourselves as viewers off from something, which is sort of appreciating humanity and the humanity of black women in all of its nuance and all of its complexity.

Dr. Joy: Dr. Gates, what are some of your favorite resources for anybody maybe who wants to dig a little deeper into like all of the things you've shared today?

Dr. Gates: Oh, goodness, let's see. I write about reality TV in my book which is called Double Negative: The Black Image and Popular Culture. I recommend work by scholar Kristen Warner who writes about reality TV and casting. Also the work by scholars Laurie Ouellette and Amanda Klein who write a lot about like reality TV in general. Amanda Klein has a really fabulous new book, it’s a cultural history of MTV which I think is like pretty great. Alice Leppert has a fantastic piece about the Kardashians and like capitalism and sisterhood. I know I'm forgetting a bunch of people and I'll be mad at myself. But those are the people who come to mind. Laurie Ouellette and Susan Murray have a textbook that I use to teach my reality TV class and it's just a collection of fabulous essays by fabulous reality TV scholars. So yeah.

Dr. Joy: I love it, thank you for those. And where can we find you? You already mentioned your book, but what is your website as well as any social media handles you'd like to share?

Dr. Gates: Yeah, my website is www.RacquelGates.com. You can find me on Twitter, Instagram, like @RacquelGates. Pretty sure it's the same thing everywhere so...

Dr. Joy: We'll find it for sure.

Dr. Gates: That's where I am.

Dr. Joy: Perfect. Well, thank you so much for spending some time with us today, Dr. Gates. I really appreciate it.

Dr. Gates: Thank you. It was so great to chat with you and be able to like wax poetic about all the reality television.

Dr. Joy: I'm so glad that Dr. Gates was able to share her expertise with us today. To learn more about her and her work, visit the show notes at TherapyForBlackGirls.com/session218. And don't forget to text two of your girls and tell them to check out the episode as well.

If you're looking for a therapist in your area, be sure to check out our therapist directory at TherapyForBlackGirls.com/directory.

And if you want to continue digging into this topic or just be in community with other sisters, come on over and join us in the sister circle. It's our cozy corner of the internet designed just for black women. You can join us at Community.TherapyForBlackGirls.com. Thank y’all so much for joining me again this week. I look forward to continuing this conversation with you all real soon. Take good care.