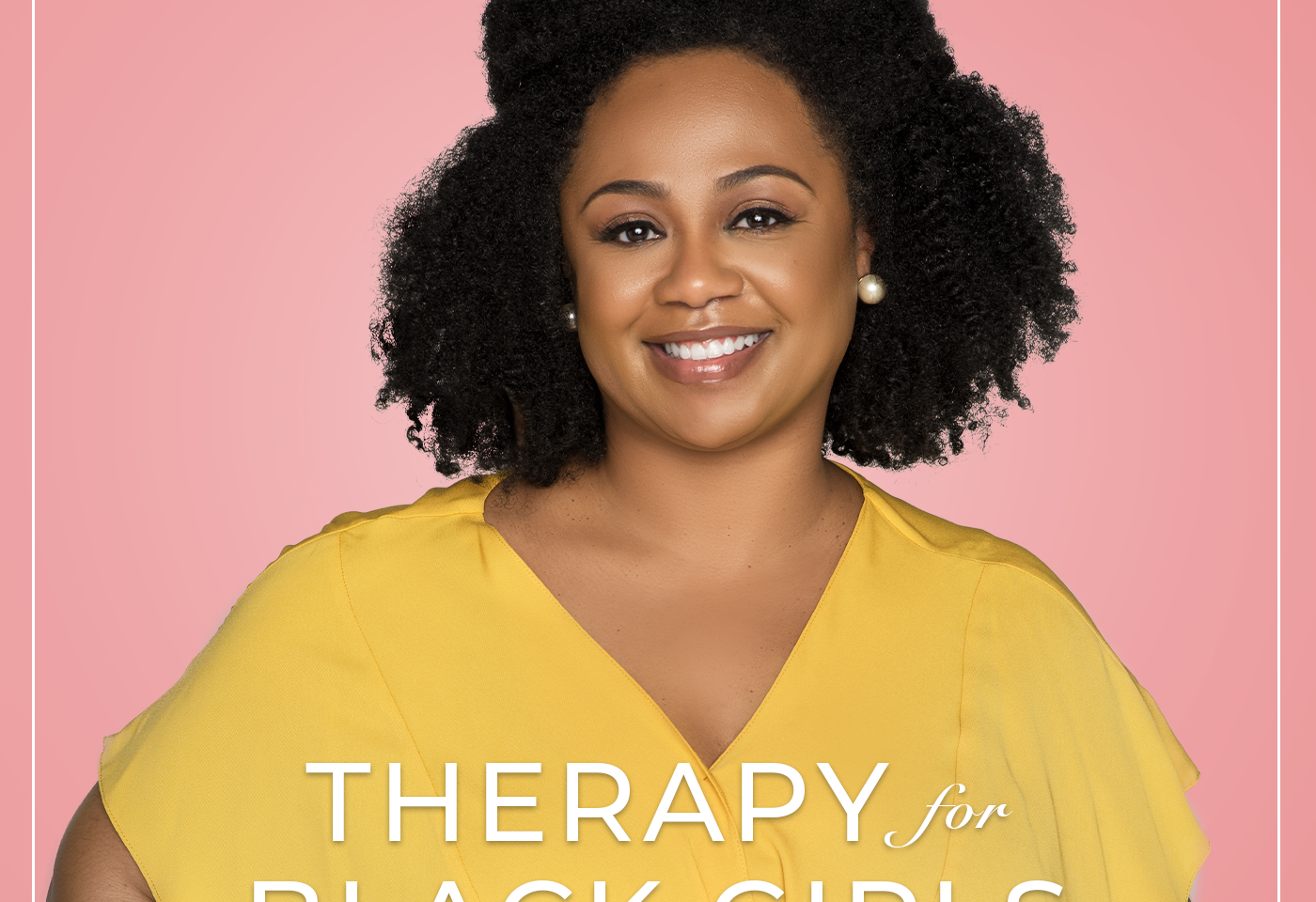

The Therapy for Black Girls Podcast is a weekly conversation with Dr. Joy Harden Bradford, a licensed Psychologist in Atlanta, Georgia, about all things mental health, personal development, and all the small decisions we can make to become the best possible versions of ourselves.

The fight for reproductive justice has become even more significant following a recent law that passed in Texas making abortions more restrictive. Now more than ever it’s important for us to be engaged in and supporting the efforts of those fighting for the rights of the most marginalized. Joining us today to share about her work in this space is Yamani Hernandez. Yamani and I chatted about what leadership looks like in this space at this moment, protecting your mental health while doing this work, what it looks like to do this work in the age of social media, and she shared ways for you to get involved in supporting this important movement.

Resources

Visit our Amazon Store for all the books mentioned on the podcast!

Support Yamani’s Work

Stay Connected

Is there a topic you’d like covered on the podcast? Submit it at therapyforblackgirls.com/mailbox.

If you’re looking for a therapist in your area, check out the directory at https://www.therapyforblackgirls.com/directory.

Take the info from the podcast to the next level by joining us in the Therapy for Black Girls Sister Circle community.therapyforblackgirls.com

Grab your copy of our guided affirmation and other TBG Merch at therapyforblackgirls.com/shop.

The hashtag for the podcast is #TBGinSession.

Make sure to follow us on social media:

Twitter: @therapy4bgirls

Instagram: @therapyforblackgirls

Facebook: @therapyforblackgirls

Our Production Team

Executive Producers: Dennison Bradford & Maya Cole

Producer: Cindy Okereke

Assistant Producer: Ellice Ellis

Session 228: Supporting the Fight for Reproductive Justice

Dr. Joy: Hey, y'all! Thanks so much for joining me for Session 228 of the Therapy for Black Girls podcast. We'll get right into the episode after a word from our sponsors.

[SPONSORS’ MESSAGES]

Dr. Joy: The fight for reproductive justice has become even more significant following a recent law that passed in Texas making abortions more restrictive. Now more than ever, it's important for us to be engaged in and supporting the efforts of those fighting for the rights of those most marginalized. Joining us today to share about her work in this space is Yamani Hernandez.

Yamani is a visionary and strategic queer African-American Buddhist leader committed to radical compassion and healing justice. She became the Executive Director of the National Network of Abortion Funds in May 2015. During her tenure, the organization has grown dramatically in size, framing, and capacity to build cultural and political power with its organizational and individual members as they remove financial and logistical barriers to abortion access by centering people who have abortions and organizing at the intersections of racial, economic and reproductive justice.

Yamani and I chatted about what leadership looks like in this space at this moment, protecting your mental health while doing this work, what it looks like to do this work in the age of social media, and she shared ways for you to get involved in supporting this important movement. If something resonates with you while enjoying our conversation, please share it with us on social media using the hashtag #TBGinSession. Here’s our conversation.

Dr. Joy: Thank you so much for joining me today, Yamani.

Yamani: Sure.

Dr. Joy: Very excited to chat with you. I wonder if you could just start by telling us a little bit about your role as the Executive Director of the National Network of Abortion Funds, and how being black and queer has shaped your experience in this position.

Yamani: I lead a national network of grassroots organizations, there's 83 members across the country who we like to say make legal rights to abortion actually possible. They help pay for people's abortions, they help get rides, childcare, housing, hotel stays, doula support, all of the things it takes to help people get to care. And so in my role, I am a spokesperson, I am a lead strategist, thinking about organizational development, infrastructure, and how to support this network of 83 members.

And to the other part about what it's been like to be black and queer in this role, I think blackness and queerness are not a monolith and I think that has been clear to me repeatedly over and over again. Sometimes I have unexpected opinions for what people would think a black person or a queer person or a black queer person is supposed to have. And I think I've learned just that the duties of my job and my employer are not the only responsibilities that I have. But also, there are so many expectations from my own community–people who look like me, people who identify with my life experience and my lived experiences–that it adds another layer to my responsibility about who I'm accountable to and when and how. So it's adds a little extra to the role.

Dr. Joy: I wonder if you could talk more about that. I mean, because there is the job but so much of your work, it sounds like, it's heart-centered and like really mission focused and community focused and it does add this other layer of like direct accountability, I think, to the community that you say you serve. So how do you feel like you've been able to manage that additional layer of accountability?

Yamani: It’s been hard at some times and other times I have had pretty proud moments. I'm the first black person to lead this organization in its nearly 30-year history. I've been in my role for six years. When I came, it was predominantly white folks on staff and we have pretty much a majority (about 75% people of color) on staff now and I feel really proud about that. Not that it's something that I dictated, but I think it's part of just like a cultural change that has happened at the organization and I feel really proud of that.

I think there's other times where, yeah, I can be disappointing, I guess. Because I think sometimes people think, oh, we hired a black person that means they're obviously going to be like a racial justice expert and they will know how to do all the latest DEI, this, that and the other. And that's not actually my expertise. I have my lived experience as a black mama and socialized as a black girl growing up, but I don't have all of those skills. So I can be disappointing to people sometimes where they thought that I was going to deliver something that is not in my job description but, you know, it's just assumed like, “oh, she's black so this is gonna happen,” and I think that can be some of the tension.

Dr. Joy: I’d love to hear you talk, Yamani, about what leadership looks like at this moment in history. Just fresh off the heels of this ruling in Texas, and so I'm just wondering like what leadership has looked like for you and what are you envisioning it looking like going forward?

Yamani: I love that question because it is very active in my mind right now. Because I think most of us are living through a period that we haven't seen before in our lifetime as far as the level of restrictions on abortion. And, I mean, I'm 43, pre-Roe days was before. It was pre-me days, I guess, but I think there's this pressure to like know the answers and to know how to solve this and there aren't any easy solutions and it's a very horrible place that we're in.

I think there's always this tension between being a national leader and we're in a network, so we have literally 83 organizations, so there's leaders at all of those organizations as well. And so I'm always trying to balance, where do I show up in my leadership at the national level and where do I really pass the mic to our local leaders, our local or state leaders who are closer to the ground and who are closer to the solutions I think that are going to be necessary? And so that to me is really about sharing power and not thinking that there's one singular charismatic leader that is gonna have all the answers. This is a group project.

And so yeah, that's hard to balance because sometimes I think in an emergency people are like, “Where's the somebody to... just give us the answer?” Yeah, exactly, and that's not how we're going to survive this. I mean, the way we're gonna survive this is gonna be us all kind of locking hands across states, cities, neighborhoods, blocks, and that is different. That's different than some of the other times we've lived through, I guess. It’s a lot more a localized problem to solve, in the absence of a federal and government solution that we should be able to rely on at this point.

Dr. Joy: And can you talk a little bit about what this moment means, particularly for black and brown and queer communities in terms of like abortion rights and reproductive rights? How are you thinking these communities are going to be most impacted?

Yamani: Well, you know the age-old saying that folks who can afford abortion will always have a way to find it. They're gonna get to it whether it means flying to other states, whether it means flying to other countries, that's always happened and it will continue to happen. The people who are going to be hit hardest by this are the people who can't afford to do that. And in this country, we know that economic suffering and racism are inextricably linked, so that'll be the people who are most marginalized–the black people, the brown people, the folks who are undocumented and cannot travel the same way that other folks can.

People who their gender identities are different, then being collapsed into like a binary of this person or that person, this sex or that sex, this gender or that gender. And so, yeah, it means being further criminalized and which is something that our communities are already dealing with. And so adding this layer of also just being criminalized for being able to actually access health care in itself is just infuriating, upsetting, depressing, all of those things.

I mean, I'm always trying to like balance the resiliency narratives. I do like to talk about the fact that we have always figured out what we needed to do to take care of ourselves. I want to always root for like our resilience but I'm also just like, when do we ever get to not be strong and have to know everything and figure everything out for ourselves? When do we have the support that we need to not have to just be in survival mode? And this is just one more time where we're going to be trying to figure it out on our own without the systemic supports that we need.

Dr. Joy: More from my conversation with Yamani after the break.

[BREAK]

Dr. Joy: Just given the past 18 months, it just has felt relentless, right? I mean, we are trying to keep ourselves safe, keep our families safe, trying not to get shot in the streets or unfairly targeted. I think this ruling in Texas just felt like, “Oh my gosh, like when do we get a break? When can we come up for air?” And a pandemic that’s still going on!

Yamani: In a pandemic that we also have never seen before where losses of childcare, levels of exhaustion, losses of employment... Before the pandemic started, we had done so much work to build the capacity of our membership that abortion funds were starting to be able to fund more people than they ever had been before. And then the pandemic hit and then the call volume for help doubled and so then, it's just like you said, this relentless kind of circle of need and exhaustion. I keep saying one of the times that our capacity is needed the most and we are wounded. I was working 20 hours a week most of 2020 because school was happening in the house and trying to do that and lead the organization, and that has been a trend for a lot of folks who have been caretaking and so it's been rough.

Dr. Joy: Yeah, so that leads me to my next question. Just like how are you taking care of yourself? Like how has your mental health been impacted doing this work, even before the pandemic but certainly right now? Like what kinds of things are you doing to take care of yourself?

Yamani: Well, I have a regular therapy appointment. I also like to describe myself as warm but boundaried and there’s just hard limits that I've had to have on. I can't work 24/7, I don't work on the weekends, I don't work in the evenings.

Dr. Joy: Warm and boundaried? I love that definition. What does that mean to you?

Yamani: It means being friendly, being kind, but also having limits and having standards. And so that means that I am not available all the time to every person and it means that my values rule my decision-making and so I'm not going to make decisions that I can't live with and that I don't feel are an integrity with who I am and what I believe. I will be kind and I will be friendly, but I'm not gonna be pushed over and I'm not gonna just do whatever anybody wants me to do.

Dr. Joy: And have you found that it's harder to do that in times of... I mean maybe it always seems like a crisis, but especially now after the Texas rulings, has it been harder to stay boundaried or more boundaried?

Yamani: Yeah, it has. And then there's like a guilt, you know, that comes with just being able to... Being like I have to stop today, I have to stop right now, I need to make dinner, I need to eat, I need to take a walk, my dog’s got to go out. It is harder because you feel like, oh, my god, like this needs everything that I can give it. But I also know that I start making mistakes when I'm tired, I start not being as friendly when I'm tired, so I'm like let me take care of the basics first. I got off Twitter in 2020 because it was years of people calling me a murderer, telling me that I should be murdered. I save a lot of those things just because I'm like, well, if anything ever happens to me, I want to have a record of the people who openly called for that.

I gave a speech in 2016 in front of the Supreme Court and somebody jumped on stage and tried to push me off so I stopped speaking in front of crowds after that. There's just like balancing a need for visibility and sort of like showing strong leadership, and also making sure that I remain alive and intact in terms of my mental health and spiritual wellness. It's a balance so I try to treat that really carefully. And I've had a real shift in that since 2018 and going to like inpatient care. I remember there was like a statement that one of the providers said that was just like “you have to organize your life around your recovery” and that's really what I've tried to do. Is just create the conditions that I felt when I had the most support and care. And it's not always popular for just like productivity but it's making sure that I'm here.

Dr. Joy: I'm glad you brought that up because it is something that I've heard lots of like highly visible black women talk about. Especially doing the kind of work that you do, there is a real dangerous and dark side to this work and so it sounds like you've been able to put some things in place to really be able to try to take care of yourself the best way that you can. But it also feels like there's this struggle, right? Because the work in some ways kind of requires you to be highly visible.

Yamani: Yeah, it's been a tension, to be honest. I think we've shifted into this space where like being on Twitter is almost required in order to build a platform or to be visible in a certain way and so, yeah, I think that was a really hard decision for me to basically take myself out of that space. But I also felt that there was enough sort of like toxic aspects of it that it ended up being the right decision for me. And I'm looking for other ways to be able to be visible, whether it's blogging or writing a book, things like that.

Dr. Joy: And how are you talking with the leaders that you lead, about like how to take care of their mental health doing this work?

Yamani: That's a great question. We have, this afternoon, a little leadership circle basically with some of the members in our network, that we haven't done as often as I would have liked. It's hopefully a space where we can talk about some of that and just like a safe space for people to be able to say that they're tired and hear validation. I think sometimes even when we can't solve a problem, we can at least validate what people are feeling.

And after a lot of those bans, the ban happened in Texas on September 1, there was a number of our member organizations that decided to take a pause for a week or decided to just regroup. And I did get like some frantic questions from some other parties that were like, “What's happening? Why are people taking breaks?” And I'm like, I support them taking a break. We have to have moments when we pause. We can't just endlessly go without ever stopping. I think Tricia from the Nap Ministry has a quote about how will we be able to experience liberation if we're too tired to know what it feels like? I hope to also validate our members taking the breaks that they need to be able to regroup, reset, replenish, in order to be able to give to the work.

Dr. Joy: Yeah, that is really important. And how have you been able to deal with some of the hopelessness, maybe for yourself and for your leaders, that sometimes comes with like this hit after hit that feels relentless?

Yamani: I think when you work on an actual hotline, a helpline, when somebody is calling and you're able to concretely get them the help that they need, it's something that really chips away at that hopelessness. And it's not something that I've done that often from where I sit, but I have done it before and I also have helped with some like logistical aspects of somebody trying to get to care. And it gives you just like a very concrete feeling of “I am doing something, I am helping. This situation was not great and now it's better.” And that's on a very micro individual level.

I think sometimes we talk about stuff in very theoretical ways but when you are actually talking to individual people and they're texting you and calling you and thanking you and saying, “You changed my life. I don't know what I would have done without your help.” Those things, I think, are what help people keep going and those are things that help me keep going for sure. Because, if you just sort of give in, you can give in to the like hopelessness, that's what the anti-choice folks want so I'm not gonna give them that. But, yeah, you have to find the small places of sweetness to counteract all of the cruelty.

Dr. Joy: In addition to your work as the executive director, you are also trained as a doula. Can you tell us a little bit more about like your training in that, what inspired you to do that, and how that informs your work as the executive director?

Yamani: Yeah, thank you for asking that. I never get to talk about that. I’m not like actively working as a doula right now but I have in the past. I went to doula training when I was leading the Illinois caucus for adolescent health and we were doing work on youth sexual health rights and identities. And we were thinking about starting a youth doula program because we do a lot of work to support young parents so we were just trying to think of what different things will be supportive. And a few of us decided, well, we can't start the program without doing the training ourselves first and so I went to the training in 2014.

It was at the time ICTC, International Center for Traditional Childbearing. I think they've changed her name since then but it was basically like a culturally specific black-focused doula training program which, man, it was really life changing for me. I've given birth twice and I had not thought critically about those experiences until I went through doula training and thought about where I had support and where I didn't have support.

And there's a group here called Chicago Volunteer Doulas and I volunteered with them just to be an on-call doula for people who were like in labor and needed help. And it was, again, one of those things that just really fed me and filled me up to concretely like go to somebody’s birth, stand by their side. You know, it's just like accompaniment, holding space for somebody and that is a lot of what abortion funds do as well.

I think even though my work is very focused on abortion, like operating from a reproductive justice framework, it's about more than abortion and thinking about birth, parenting, all of the experiences that make up our reproductive lives. At least mentally, those things are all connected to me and so I try to remember that in my work and remember the individual people that I'm working with.

Dr. Joy: More from my conversation with Yamani after the break.

[BREAK]

Dr. Joy: Can you give us a breakdown of what people are talking about? What do we mean when we say reproductive justice?

Yamani: Reproductive justice is a framework that was started by black women in the early 90s, that is really linking reproductive rights with social justice and complicating the “pro-choice” narrative. And saying like our choices are political actually, and our choices are also impacted by our societal experience and our access to justice. So it's not just about abortion but the right to have a child, the right to not have a child, and also the right to parent the children that you have without interference. We want our children to grow up.

You know, as a mom of black sons, I'm just like, yeah, I want them to be able to grow up and I also see the police violence as an issue that impacts whether people decide to parent at all. And so you can't just say like abortion is for people who don't like children or something like that, it's not that simple. Most of the people who have abortions are already parenting and don't have the resources that they need or the supports that they need to have the families that they want to have. So reproductive justice is a broader framework that is about trying to ensure that all of us have the rights and resources to decide if, what, and how we have a family.

Dr. Joy: I think that that's helpful to hear because I think sometimes people hear reproductive justice and they only think abortion when there are so many other pieces to the puzzle.

Yamani: Yeah, and they're related. I had a miscarriage in 2018 and I started to pay attention more to like miscarriage narratives and abortion and I realized also, oh, this is what happened. When I was in the hospital, I got my discharge paperwork and it said abortion on it. And I was like, oh, I didn't have an abortion, I had a miscarriage. Then it just sent me down this like spiral of like, oh... Like it actually is technically called an abortion but because that word has been so politicized, we can't talk about pregnancy loss or the ending of a pregnancy without it being this supercharged conversation.

And I started to realize that there were these hospitals that folks will be going for miscarriage management care and being turned away because the help that they needed is very similar to what it takes to perform an abortion. So yeah, we can't really separate. Like some people who are like, a miscarriage, somebody didn't mean to end their pregnancy. And it's like, yeah, okay, but they're still dealing with the same barriers to care that people who intended to terminate their pregnancies and that's not fair. Everybody should have access to the same level of care.

And the same thing with birth. All of these black women who are the mortality rate, the black women who are dying in childbirth. And you can't separate that from whether you decide to even carry a pregnancy to term. Like finding out you're pregnant and then also reconciling how many black women are dying from childbirth, people are like, “I don't want to do that. No thank you.” So it's all connected and related and I don't think we get to talk about those connections enough. All these conversations end up being like very siloed and so I really welcome opportunities to talk about it all together.

Dr. Joy: Are there other things that you feel like are left out of this conversation, or these conversations, that you would love for people to know? Is there an additional nuance that is often left out that you think, oh, this could be helpful for people?

Yamani: I think that we definitely as a society are starting to gain more nuance in talking about sex and gender but we still have a long way to go. I feel really ambivalent about my own gender and I found out, after a long time of like having this existential feeling or thinking about it, that I am intersex. I sometimes feel frustrated in conversations about reproductive health rights and justice because it is so binary in how we talk about it and there's been sometimes debates over like whether we can use people versus women. Or recognizing that people of all sexes and people of all genders are having abortions, are having pregnancies, and so like more nuance about that.

And I think that that leads me to the other thing that I wish we talked more about which is just sex ed because there's just so much ignorance. I don't mean that in like a pejorative way; I just mean like people just don't know and they've never been taught. I don't think that's by accident but, yeah, we don't have comprehensive sex ed in this country, it’s wildly variable from state to state, city to city. And a lot of these politicians and lawmakers that are making decisions don't even know how the body works, that's why you get politicians saying stuff like, “Oh, if somebody is raped, then the body just shuts down pregnancy. It doesn't happen.” It’s just like what are you talking... what... where did you get that? There are some really great organizations that are putting a lot of work into sex ed, but I think it should just be a lot more universal priority.

And thinking about young people, the anti-choice folks really use young people, unfortunately, as a weapon. They trot young people out, they take them on field trips and take them outside of abortion clinics and have them stand outside, shaming the people going into those clinics–by the dozens, by the hundreds sometimes. They'll take like a whole camp, a whole summer camp, and that's their activity. I think that's terrible, the way that they are politicizing young people in that way. But I also think there's just a huge opportunity for us to like counteract that in teaching young people about their bodies and talking honestly about sexuality, gender, reproduction, all of the things. And yeah, a lot of us are afraid to do that so I just think I would like to see more sex education.

Dr. Joy: Yeah, and it sounds like it definitely would help to cut down on at least some of the confusion and, like you mentioned, the ignorance that people just really don't have the correct information sometimes.

You mentioned that the need and the demand for community services really increased during the pandemic even while those of you doing the work have really felt exhausted. What would you say that organizations need most right now, like that are doing this work?

Yamani: We need money, people, and legal support. Honestly, those are the biggest things. We need money because there's a lot more... or I should say our members need money because when you have a ban like the one in Texas, that means people need to leave the state. And even like driving to the next states, those most immediate states can be overwhelmed so sometimes it's even more prudent to get on a plane and fly to Illinois or somewhere else, and so that's more expensive. That's more expensive than somebody giving a ride so I've been hearing that they expect five times more, they need five times more than what they have been giving away to support that need.

And then people, just case management and volunteers are really important but I don't think people know that a lot of abortion funds are volunteer-run. That's something that has been shifting over time with a lot of effort and fundraising, to try to get people to be paid for their labor. Six years ago, 25% of our members had paid staff; now about 75% do have at least one paid staff. But still, there's like a lot that still just have only volunteers and so volunteer management and being able to also have enough people to train people to be able to let people rest, is important. Like I said, the sort of like being able to relay, pass the baton to somebody. Okay, you take it I'm gonna rest. You take it and I'll take it back.

And then I just think like the legal support is really important because all of this criminalization that is happening. There's a repro legal defense line that was created out of If/When/How, an organization in our movement, which is going to be really important.

I will add one more thing which is just like talking about the issues and not causing more harm by talking about them. I think immediately after the bans, people were using phrases like Texas Taliban and talking about The Handmaid's Tale and all of this, and we don't have to make references to folks outside of the country. If anything, we can reference the KKK and the white supremacists that make these laws what they are. But yeah, I think just like not adding more stigma to the issue and talking about it in a way that centers the people most impacted which (like we talked about earlier) are like black and brown folks and people who are struggling to make ends meet.

Dr. Joy: What advice would you have for young people who are wanting to get involved in the reproductive justice movement?

Yamani: First of all, come on, we need you. Come on, there's lots of opportunity for sure. But I think also there is a new breed of “worker” where like people are not willing to sacrifice their entire lives for their employment and I really support that. So my advice to young leaders is don't collapse yourself into your job. Make space for the other things that you care about and the other parts of you that are important and, yeah, be a whole person. Give what you can give but don't give everything away.

Dr. Joy: Yeah, that sounds very important. Where can people find more information, Yamani? If they want to volunteer or donate or get involved in any of the organizations, where should they go?

Yamani: Our website is AbortionFunds.org and we have a tab called “Need an Abortion.” If you click on there, there's a list of every abortion fund in every state. So you could go to our website to find all of the abortion funds, you can find one that's local to you, you can donate, you can volunteer, all the information is there. All of our socials, it's the same across Twitter and Instagram, AbortionFunds, basically @AbortionFunds. And Facebook, National Network of Abortion Funds.

Dr. Joy: Perfect. Well, thank you so much for sharing this with us. I appreciate it.

Yamani: Sure. I appreciate you having me.

Dr. Joy: I'm so glad Yamani was able to share her expertise with us today. To learn more about her work or check out the resources she shared, visit the show notes at TherapyForBlackGirls.com

/session228. And don't forget to text two of your girls and tell them to check out this episode as well. If you're looking for a therapist in your area, be sure to check out our therapist directory at TherapyForBlackGirls.com/directory.

And if you want to continue digging into this topic or just be in community with other sisters, come on over and join us in the Sister Circle. It's our cozy corner of the internet designed just for black women. You can join us at Community.TherapyForBlackGirls.com. Thank y’all so much for joining me again this week. I look forward to continuing this conversation with you all real soon. Take good care.